Aviator

-

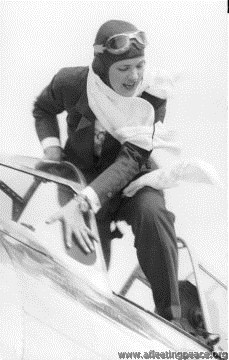

Cochran, Jacqueline

Jackie Cochran

b. 11 May 1906 (as Bessie Lee Pittman) near Mobile, Alabama

b. 11 May 1906 (as Bessie Lee Pittman) near Mobile, Alabama"Jacqueline Cochran's earliest memories are of life with a foster family on what she called "Sawdust Road," but what was, in fact, a lumber mill town in northern Florida. In her autobiography she remembered having no shoes until she was eight years old, sleeping on a pallet on the floor and wearing dresses made of cast-off flour sacks. As a child she was hired by a beauty shop owner, and by the time she was 13, she was cutting hair professionally. In the 1920s she became one of the first women to master the newly invented permanent wave. But one of the customers, noting Cochran's spark, encouraged her to do something more serious with her life. With very little formal education, Cochran enrolled in nursing school.

Even though Cochran completed three years of training to be a nurse, she never quite adjusted to the profession. In her autobiography, she remembers not ever getting "comfortable with the sight of blood." She constantly had to resist the urge to hand in her notice, reminding herself that a nurse was more valuable than a beautician. But she was never convinced, and an experience delivering a baby to an impoverished mother in Florida helped drive her back to the beauty trade. She remembered three children were sleeping on pallets next to the woman giving birth. "There I was with neither the strength nor the money to do the smallest fraction of what needed to be done to make those lives better... . In a beauty shop the customers always came in looking for a lift. And unless I really screwed up," she concluded, "they left with that lift."

Her next job as a beautician at Antoine's in New York's Saks Fifth Avenue brought Cochran into her future husband's world. At a dinner in 1932, the dashing millionaire financier Floyd Bostwick Odlum advised Cochran that if she were ever to realize her dream of setting up her own cosmetics firm, she'd need wings to cover enough territory to beat her competition. Cochran took the advice to heart, and that summer she learned to fly. "At that moment, when I paid for my first lesson," Cochran remembered later, "a beauty operator ceased to exist and an aviator was born."

Macrobertson Air Race in 1934

Excerpt from: "JACKIE COCHRAN, An Autobiography" by Jacqueline Cochran & Maryann Bucknum Brinley

"Gee Bee stands for Granville Brothers, a Springfield, Massachusetts, airplane company which made fast, unstable, dangerous planes in the thirties. The nearly cute nickname is a sham. They were killers. There were few pilots who flew Gee Bees and then lived to talk about it. Jimmy Doolittle was one. I was another.

I tell you all this as a prelude to my story about the London-to-Australia race. I flew a Gee Bee, the QED Gee Bee, but a Gee Bee nonetheless. The QED was Latin for "Quod Erat Demonstrandum" and came from the designers who translated that as "Quite Easily Done." It was not easily done, however. The crazy QED violated basic rules of aerodynamics.

Clyde Pangborn had entered his name in the race, hoping to find himself in a Gee Bee but, because of problems at the factory as well as an offer from Roscoe Turner, who had never flown over oceans before and knew that Clyde had, the QED was still sitting in the hangar, almost ready to go. Clyde had joined Roscoe's team but was still the registered owner of an entry.

He had the official right to name an alternate crew, and I knew it. Sitting in New York, after my conversation with Royal, searching for a way to stay in the race, I remembered Clyde's QED and made all the right calls.

Granville Brothers knew me because I myself had approached them earlier in the game but had changed my mind when I compared it with the chance to be in a Northrop. Jack's planes were so streamlined and beautifully fast for their day.

But any plane was better than no plane. I bought the Gee Bee with a little help from my friend Mabel Willebrandt. Granville Brothers were pleased because they were anxious to make a name for themselves in such a prestigious international contest. They even offered to send mechanics along to complete the plane en route to London on the ship.

In the meantime, I had Wesley Smith and Royal Leonard take some of the sophisticated equipment out of the Northrop Gamma so we could install it in our Gee Bee.

We had four hours to make the official arrangements with the London officials. I needed what was called an airworthiness certificate, numerous permissions to fly over all those countries, not in a Gamma but a Gee Bee, and Mabel turned on the steam. Mable even convinced a Department of Commerce official to go along on the boat to do the necessary testing.

Landing lights, flares, radio equipment - we planned to install as much as we could as we crossed the Atlantic, in spite of storms and seasickness. Not much would get done as it turned out.

All this was done by telephone. I never set eyes on that Gee Bee until I arrived at the airport near Southampton, England, and tried to fly it to the field where the race would commence, twenty-four hours later. It was a disaster and still incomplete. The other disastrous aspect was the tremendous publicity surrounding the contestants. I had never experienced anything like it. I never sought publicity like that in my life because mostly it's a waste of your time. And I didn't like the scene there in London one bit.

The press kept rumoring about the mysterious American woman entry, but there was nothing mysterious about my whereabouts or doings. I had a tricky, incomplete plane to contend with. In the meantime, Clyde Pangborn was giving me trouble and demanding that I pay him for the transfer of his entry. After all the anguish that Gee Bee had caused me - at that point I had no idea my troubles were just beginning - he had some nerve asking for money.

I was furious. And I told him so. If I had been a man, we would have gone out behind the hangar to fight it out....

The starting point the next morning was a nearly-completed Royal Air Force base at Mildenhall, sixty miles north of London. The lord mayor of London was there promptly at 6:30 am to drop the official white flags. Planes took off at 45-second intervals, and the famous team of Mollisons - Amy was a wonderful pilot and flew with her husband - were first. Wesley and I were fourth in line and had been warming up the engine, but as soon as we were airborne, the plane sort of staggered, dipped slightly, and I knew we were in for a real ride.

Neither of us knew that Gee Bee well enough. We recovered speed, however, and we were serious about sticking with it.

The haze was horrible and I was happy Wesley had been such a nag about my instrument training and Morse code lessons. This race, however, was actually the first and last time I relied on Morse code.

After all the hullabaloo in America about this contest, only three American-crewed entries remained: Roscoe Turner, the United States speed king at the time; Jack Wright, a stunt pilot from Utica, New York; and me. When you compared the elaborate preparations I had made for the flight - sending specialists ahead on the route with automatic refueling devices, flares, spare parts, personal items, extra instruments - as well as the whole debacle with my Northrop Gamma - to Jack Wright's simplistic attitude, I really wondered.

All Jack wanted to do en route was to "fly this plane while it's still mine". It was a tiny Lambert Monocoupe with a single 90 horsepower that hummed along. Who had more sense: him or me?

I had even sent clothes along to Melbourne so I'd have something to wear to the festivities.

But I wasn't alone with my big thinking. Roscoe Turner had gone into hock to buy a Boeing transport plane he called the "Nip and Tuck". Then because of rough weather he hadn't been able to get it off the ship at Plymouth. They had to take it over to France, to Le Havre, where the French tried to make him pay import duty of $20,000. He got around that but had to unload the plane, assemble it, and fly it back to England in time.

That was funny about all of our best-laid plans was that the Europeans had been sullen and some of them openly angry about what they believed to be a Yankee conspiracy to walk away with all the prize money.

Little did they realize. My Gee Bee was the fastest plane in the race, I believe, but right from the start I realized that it wouldn't be speed that would win.

Jackie and her co-pilot Wesley Smith were forced down by engine trouble in Rumania.

In 1953 she became the first woman to break the sound barrier in a F-86 Sabre jet fighter, earning the title 'America's Fastest Lady'.

d. 9th August 1980 in Indio, California, aged 74

-

Cochrane, Ralph Alexander

Ralph Alexander Cochrane

b. 1893

later Air Chief Marshall The Hon R Cochrane.

In 1930, he was at the RAF Staff College.

-

Cockerell, Stanley

Capt Stanley Cockerell AFC, Croix de Guerre (Belgium)

photo: 1930, aged 33

b. 9 Feb 1895, the 'willowy' Vickers chief test pilot - he and his assistant Frank Broome (q.v.) were known as the 'Heavenly Twins'.

RFC in WWI (7 victories).

Married Miss Lorna Lockyer in 1921.

Killed in WWII: on the 29th November 1940, when the Running Horse(s?) Pub in Erith was bombed.

His 6-year-old daughter Kathleen also died and they were buried at the church of Saint Mary, Sunbury on Thames.

Lorna also died during the Blitz. Some children survived and were split up and most were adopted, losing touch with each other.

-

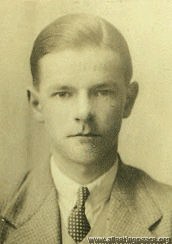

Comper, Nicholas

Flt-Lt Nicholas Comper

in 1916, aged 19

in 1916, aged 19lecturer at the Cranwell Engineering Laboratory, ex Cambridge University.

Designer of the Comper Swift; died in 1939 after a practical joke went wrong

-

Cook, Arthur Harry

Mr Arthur Harry Cook

in 1932, aged 23

in 1932, aged 23b. 29 May 1909 in Bletchley, Bucks; educated at Bletchley Grammar.

In 1932, worked for Beacon Brushes Ltd, Bletchley; apparently, brush-making is Bletchley's oldest large-scale industry and Beacon Brushes was formed in 1926 by 'Jack Cook and his sons'. See http://www.discovermiltonkeynes.co.uk

Arthur's father was called Arthur John Dennis Cook, but anyway by 1943 our Arthur was 'Works Manager and Joint Managing Director' of the firm, based at Church Farm, Wavendon, Bucks. Which is near Bletchley (that's enough mentions of Bletchley).

Air Transport Auxiliary in WWII

d. 1980

-

Cotton, Frederick Sidney

Flt-Lt Frederick Sidney Cotton OBE

in 1920

in 1920

in 1916, when a Flt Sub-Lt in the RNAS

b. 17 June 1894 in Bowen, Queensland, Australia

RNAS in WWI; he invented the 'Sidcot' flying suit, which was standard issue in the RAF until the 1950s.

There was a curious period in early 1920 when four sets of people tried to fly from Cairo to Cape Town; not for any particular prize or competition, but just because they fancied being the first to do it. Frederick Cotton and his engineer Capt W A Townsend flew a DH.14a and were the least successful of the lot, making a forced landing in southern Italy and writing off the machine before they even got to Cairo.

In the winter of 1920-21 he and Alan Butler were in Newfoundland, "doing some extremely useful work surveying, spotting for seals, etc", and the following September they both competed in the Croydon Aviation Meeting.

In late 1922 he had "exciting times" in flying from Newfoundland to the newly-discovered gold fields at Labrador. He then settled into being a pilot in Newfoundland, although he came back to England occasionally, for example for the 'Portsmouth Trophy Race' round the Isle of Wight in 1934, in which he came second.

Married 3 times, clever, sometimes quite rich (although he died penniless) and rather, er, "unorthodox" (bleedin' awkward, by the sounds of it), he spent WWII as an unofficial advisor to the Admiralty, especially involved with photographic reconnaisance and airborne searchlights.

d. 13 Feb 1969 in London

-

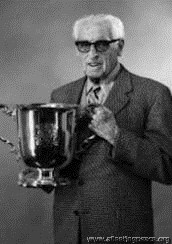

Courtney, Frank Thomas

Capt Frank Thomas Courtney

photo: 1972, holding the King's Cup at the RAF Museum, Hendon, aged 78

photo: 1972, holding the King's Cup at the RAF Museum, Hendon, aged 78An Irishman and early aviator; he test-flew the prototype D.H.18 - de Havilland's first purpose-designed airliner - in March 1920 and often flew it in service. Also flew in the 1929 Cleveland National Air Races. Also flew the Cierva autogyro in 1925, (but not in the King's Cup)

-

Crossley, Fidelia Josephine

Miss Fidelia Josephine Crossley

in 1930, aged 25

in 1930, aged 25

At Combermere Abbey in 1932

At Combermere Abbey in 1932'Delia', born 1st June, 1905, the daughter of Sir Kenneth Irwin, 2nd Baronet Crossley, Chairman of the Crossley Car and Engineering companies in Manchester.

In 1919, the Crossley family moved to Combermere Abbey, Whitchurch, Shropshire and her father held the offices of High Sheriff and Justice of the Peace for Cheshire. These days, although it continues in private ownership, Combermere Abbey ‘welcomes visitors in groups or on specific days by appointment’. It has been described as ‘one of the most romantic places in Europe’ .

Gained her pilot’s licence in 1930. She only competed in the King’s Cup once - in 1931, when she was the only woman competitor to finish, a gallant 20th out of the 21 finishers (another 20 dropped out on the way, don't forget).

August 1931 found her in Dublin; "Among the visitors was one who deserved especial mention, and that was the intrepid Miss Crossley, who put up such a fine show in the recent King's Cup race. She flew the long way round, and is now continuing to tour the country."

In 1932, she visited India, where "we hear she has been doing a considerable amount of flying." In fact, she competed in the Viceroy Cup (India's version of the King's Cup) with 5 other English pilots and 6 from India.

She also competed in several other races and gatherings, e.g.

- Ladies event at Reading (May, 1931) - the other competitors were Amy Johnson, Pauline Gower, Dorothy Spicer, Gabrielle Burr (Patterson), Susan Slade, and Winifred Spooner - a historic gathering indeed.

- London-Newcastle, August 1932, in Comper Swift G-ABUA; finished 11th of 18

- Yorkshire Tophy Race, September 1932 (not placed);

- Heston-Cardiff, October 1932, also in Comper Swift G-ABUA; finished 3rd of 9

- the second 'Bienvenue Aerienne' in France (July 1934)

Delia with C C Grey (editor of 'The Aeroplane'), Mrs Grey, Connie Leathart and others.

She also entered her Comper Swift in the 1932 King's Cup Race, but withdrew before the start, and seems to have retired from air racing in 1935.

On the outbreak of WWII, Delia became an ambulance driver for the London County Council, but then applied for a job as a ferry pilot for the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA).

Air Transport Auxiliary in WWII

She married Geza O Schubert in September 1949.

Fidelia’s de Havilland D.H. 60G Gipsy Moth G-AAKC (seen here behind G-AACY) was first registered in July 1929, and she bought it from Malcolm Campbell Ltd, the Moth distributors for the UK. She eventually passed it to her father, and it was then sold in South Africa in 1937.

Her Comper Swift was first registered in February 1932 to J D M Gray, and she sold it to Arthur H Cook. It ended up in Indonesia.

... and there's a splendid page about 'Combermere's Pioneering Aviatrix Delia Crossley' here, written by the archivist at Combermere Abbey. -

Crossley, Winifred Mary

Winifred Mary Crossley

in 1934, aged 28

in 1934, aged 28b. 9 Jan 1906 in St Neots

Winifred spent more than five years towing banners for aerial advertising and as a stunt pilot in an air circus. She served for the full 5 years of the ATA in WWII.

Separated from her first husband; in 1943 she married airline captain Peter Fair, head of BOAC-owned Bahamas Airways in Nassau."

Died in 1984 in Aylesbury, Bucks.

-

Cubitt, William Partridge

William Partridge 'Pat' Cubitt  1927

1927b. 26 Oct 1898, Bacton, Norwich

A Farmer, of 'Bacton Abbey', Norwich

In July 1931, the owners of the Norfolk and Norwich Aero Club decided that they would like to "repay a little of the hospitality they had had from the hands of other private owners of other clubs.

Some forty aircraft arrived from all parts of the country, and were welcomed by Messrs Gough, Surtees, Brett and Cubitt, bunches of tickets were shoved into their hands, and they were told to jolly well enjoy themselves... which they did!!

On the Sunday they went over to Pat Cubitt's place at Bacton on the coast, and were treated to a picnic lunch on the sand dunes.

d. 14 Dec 1955 leaving £48,748 5s 5d (having inherited about £62,000 in 1929)

-

Cumming, William Neville

FLt Lt William Neville Cumming DFC b. Edinburgh 22 Sep 1899

flew in N Ontario 1926-7; 1926-30 on the trans-prairie night mail; Imperial Airways from 1930

RAeC Certificate No 22856 in 1947, by which time he was a Company Director and lived in Epsom, Surrey.

-

David, Edward Hugh Markham

Flt-Lt Edward Hugh Markham David I think this must be Flt-Lt (later Sqn Ldr, Wing Cmdr from 1939, Grp Capt, CBE) Edward Hugh Markham David, who served in the Navy in WWI, as a cadet at Osborne in 1914 and Dartmouth, and a midshipman in the 'St Vincent', 'Whiteley', and 'Revenge'. He was one the very first tranche who trained at RAF Cranwell when it opened in 1920.

b. 10 Jan 1901 in Monmouth, he was posted to Iraq in 1921-25 and Aden in 1932-4, then became Adjutant of 604 (County of Middlesex) Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force.

DFC in September 1941; retired and moved to Malta after WWII; his daughter Diana Elizabeth Markham married in 1952.

d. 1957

-

Davies, Cyril G

F/O Cyril G Davies

Partnered Lt-Cmdr E M Hillin the MacRobertson Race

AHSA_1985_AH_Vol_24_No_1-2 says:

"The pair who had flown together in the Fleet Air Arm became known as “Burglar Bill and the Missionary”. Davies earned the title of the “missionary” no doubt because since leaving the R.A.F. some time previously he had been running a shelter for destitutes in the West End of London.

-

Dawson, Wilfrid Leslie

Flt-Lt Wilfrid Leslie Dawson

in 1917, when a 2nd Lieut., RFC, aged 27

in 1917, when a 2nd Lieut., RFC, aged 27b. 2 Apr 1890 in Huddersfield.

One of the first tranche of cadets at Cranwell when it opened in 1920.

Posted to RAF Staff College, Andover from January 1934, for 'Staff College Course No 12', then posted to 'Headquarters, Palestine and TransJordan' the following year.

Sqn Ldr from 1936. Married Elizabeth McIntyre, and their daughter was born in the Government Hospital Jerusalem in 1936, while he was also learning 'colloquial Arabic'.

216 (Bomber Transport) Sqn in Egypt in 1937, Wing Cmdr from 1939. In December 1939 he was one of 6 who survived the crash of an Imperial Airways airliner which crashed in the Mediterranean (5 died).

Grp Capt and CBE in 1943; Air Commodore and CB in 1945; Air Vice Marshall in 1948; Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Operations at NATO in 1953.

-

de Havilland, Geoffrey

Capt (later Sir) Geoffrey de Havilland O.M. K.B.E A.F.C Hon.F.R.Ae.S

1911, aged 29

1911, aged 29  1936, aged 54

1936, aged 54Geoffrey de Havilland - Wikipedia has his story -

de Havilland, Geoffrey Raul

Mr Geoffrey Raul de Havilland

1936

1936Geoffrey Junior, aka 'Young D.H.' born in 1910 and learnt to fly at Stag Lane at a tender age. Took over as chief test pilot at de Havillands when Bob Waight was killed.

Second Brit to fly a jet-propelled aircraft on its first flight, the Vampire in 1943. Killed when the second DH108 Swallow broke up and crashed in the Thames estuary in 1946.

Flight 18th April 1946

As a test pilot young D.H., as he is universally called,has not an exceptionally long history. He took over the chief test pilot's position in October, 1937, when R. J. Waight unfortunately lost his life on the T.K.4. Being, however, the son of his illustrious father, Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, who designed, built and test flew his own aircraft from 1911 onwards, young Geoffrey can be said to have been ''in the industry'' from the very cradle. It is not generally known that Sir Geoffrey took his R.Ae.C. ticket No. 53 in February, 1911, on the second machine of his own design and construction, and that he has made many of the first flights on new D.H. types right up to the Moth Minor in 1938.

Geoffrey's first flight is lost in the dim past, but certain it is that at the tender age of six he was flying with father at Hendon in a D.H. 6 (also known as the Clutching Hand). When 18 years of age he left school and came to de Havillands as a premium apprentice for 4 years and learnt to fly on Moths at the firm's reserve training school. After spending two years in the drawing office—much of the time being spent looking out of the windows envying the pilots—he joined the Air Operating Company, who were doing a lot of air survey work in South Africa. This, however, gave him but very little flying, and at the end of six months, he came back to England to become a flying instructor to the D.H. Technical School. The aircraft were wooden Moths built by the students. In 1929 he took his B licence; a very simple business in those days. Some 20 or 30 hours' solo flying, a little cross-country work, a simple "Met" exam, and about one hour's night flying at Croydon was sufficient to qualify.

In 1934 Capt. Hubert Broad was chief test pilot of de Havillands, and Bob Waight looked after the production side. There was so much work, however, that Geoffrey was given the opportunity to lend a hand testing Tiger Moths, Dragons, Rapides, Express Air Liners, and Hornet Moths.

Broad left the company in 1935 and Waight took over, starting, with the Dragonfly and later the Albatross. It was during the period when the prototype Albatross was going through its development flying that Waight lost his life, and de Havilland took over as chief test pilot. Nobody could have taken on a more interesting or more complex job because the Albatross was completely experimental from tip to tail. Engines were new, construction was new, and the layout was extremely advanced.

He had a curious experience on the Albatross. While its strength was ample for all flying loads, some unfortunate drilling had weakened the fuselage under ground loads, and shortly after landing from a test flight the machine broke in halves on the ground.

When war broke out lie was busy testing Oxfords and Flamingoes, but when things became desperate at the time of the Battle of Britain, de Havillands did a big job doing emergency repairs to shot-up Hurricanes.

Dick Reynell of Hawkers came over and gave Geoffrey the "know how" on Hurricanes. A little later Dick went out on operations with his old squadron (No. 43) and was, unfortunately, shot down.' He was an excellent test pilot and a gallant gentleman.

Improvised Runway

Geoffrey flew the first Mosquito at Hatfield on November 21st, 1940, but he is more proud of the first flight of the prototype Mosquito fighter. This was built at a dispersal factory with no airfield. To save some six week's wasted time in transport and re-erection at Hatfield, Geoffrey used local fields by having bridges built over ditches to give him a 450yd run for take-off, and then flew the fighter to Hatfield.

He is, of course, one of the only two men in Britain to have made first flights on jet-propelled aircraft. The Vampire was flown for the first time on September 21st, 1943, but Geoffrey had already flown the Gloster E.28 at Farnborough. The first airing of the Vampire proved it to be a tribute to the D.H. design and aerodynamics staff, as it behaved almost exactly as they had forecast. There was, however, somewhat of an aileron overbalance which limited the speed to 250 m.p.h. and a rather severe tip stall.

Geoffrey de Havilland had made a number of investigation flights on Mosquitoes for compressibility effects, but on the Vampire he has done extensive work. The Vampire, under the effects of compressibility, executes a series of sudden high-speed stalls: the path of the machine is similar to an artist's conception of a streak of lightning, and unless the pilot is strapped-in tightly he is likely to be knocked out by hitting the cockpit roof.

Geoffrey, with another pilot, has flown the Vampire in tight formation at over 500 m.p.h., and to investigate snaking, which is causing considerable trouble on most jet aircraft, he has flown the Vampire with rudder locked.

Like most of the test pilots, he is living on borrowed time, they having at some stage of their careers had close shaves. Strangely enough, Geoffrey's nearest go was on about the mildest type he ever flew. It was the first production Moth Minor. The prototype had completed its spinning tests, and the same tests on the production model appeared to be only a matter of form. He was flying with John Cunningham (now Group Capt., D.S.O.,D.F.C., and test pilot for the D.H. engine division) at the time. The Minor was put into a spin at 5-6,oooft, but after it had failed to come out in five turns and the engine had stopped, a panic decision was made to abandon ship.

Test-flying a Hurricane, too, almost saw him off. This particular aircraft had had a gruelling time in the Battle of Britain, and the whole canopy came off at 4,000ft.hitting him in the face as it blew backwards. At first blind through the amount of blood in his eyes, he flew more by instinct than anything else until he found he could get a little relief by holding his face close to the instrument board. The blood dispersed a little and he was able to land through what appeared to be a thick yellow haze. He wears the scars across his nose to this day, and there was a terrible moment during that flight when he thought he was really blind.

On another occasion the oxygen bottle contained only compressed air, and the effects from this were at first blamed on the previous night's party.

At the other end of the scale was the test of the T.K.5, a tail-first aircraft built by the technical school. Impecunious at the time, Geoffrey had already mortgaged the bonus for the first flight. Imagine his consternation then when, after roaring the whole length of Hatfield airfield, the machine showed no sign of lifting. The forward elevator was ineffective. The T.K.5 never did fly and was finally abandoned.

In the days of peace before the war Geoffrey de Havilland was to be seen at all the air meetings and twice finished 4th in the King's Cup Race flying the TK1 and TK2.

-

de Havilland, Peter Jason

Mr Peter Jason de Havilland  1931, aged 18

1931, aged 18middle son of Geoffrey; both his brothers were killed in flying accidents, but he survived and published his father's autobiography in 1979 -

Denman, Roderick Peter George

Roderick Peter George Denman

b. 1894

A descendant of William the Conqueror, apparently.

With the cast of 'The Blue Squadron' in 1934 - l to r: John Stuart, RPG Denman, 'Doc' Salomon (Studio Manager) and Greta Hansen.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blue_Squadron_%281934_film%29

A Civil Servant (Board of Education) who then worked for Airwork - by 1936, a director of Heston Airport. He seems to have specialized in wireless equipment.

M.A. (Cantab); member of the Old Etonian Flying Club; he was also a member of 'the Listeners', who won a spelling bee against the BBC in 1938. He was one of the few people who made no mistakes!

Later a Lt-Col in the Royal Corps of Signals.

Killed in WWII; 20 November 1941 in Libya, aged 46.

-

Diamant, Albert Marc

Mr Albert Marc Diamant  1932

1932b. c.1898. From Warfield, Berkshire.

Flight, 1939: "Capt. Mark Diamant has been appointed as the new general secretary of the Guild of Air Pilots and Navigators. He has been associated with the work of the Guild almost since its inception. He was a [WWI] pilot, and was for some five years the manager of the aviation department of the Dominion Motor Spirit Co. Capt. Diamant is well known in the flying club world and is, if we remember correctly, actually a member of some dozens of clubs all over the country."

Killed in WWII: 30th January 1942, when a Wing Commander, 24 Sqn RAF(O); his remains were cremated at Oxford

-

Dickinson, Vincent Neville

Mr Vincent Neville Dickinson Father: Frank Dickinson, a Merchant, Mother: Sarah Jane [Bayley]

2nd-Lieut, RFC, RAF in WW1; Pilot Officer from 20 Nov 1923

He was one of two pilots who inaugurated the Belfast to Liverpool Daily Air Service in April 1924 (the other was Alan Cobham), He started out at 05:30am in his D.H. 50, but the weather was so bad he could get no further than Southport Sands.

m. 18 Nov 1923 in Richmond-upon-Thames, Marjorie Winifred [Lloyd-Still] (1 daughter, Katheen b. 1926)

Elected a Member of the Royal Aero Club in June 1925

Formed Aero Hire Ltd in 1927, based in Birmingham, to "establish, maintain and work lines of aeroplanes, seaplanes and taxi-planes and aerial conveyances, etc. (later co-owned, with L W van Oppen,)

Competed in the King's Cup in 1929, flying G-EBTH, a DH.60X Moth. He was forced to retire at Blackpool.

Hon. Secretary and Chief Instructor, Hertfordshire Flying Club, St Albans in 1932

He owned G-EBZZ, a 1928 DH60 X Moth, which crashed at Stansted Abbots 23 Jun 1934

One reported accident:

- 14 Mar 1939, flying G-AEDD, a 1936 Avro 504N belonging to Publicity Planes Ltd; he hit a fence and crashed at Calderfields Farm, Walsall, after engine failure.

Address in 1939: 'Muree', Queen's Rd, Sandown, Isle of Wight

Briefly (5 Jun to 5 Jul 1940) a pilot for the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA)

Sub-Lieut in the Royal Navy from 15 Jul 1940

Address in 1962: 10 Oakwood Rd, Rayleigh, Essex

d. 3 Sep 192 - London

Page 5 of 23