| Race No | Pilot(s) |

Plus |

Result | |||||

|

Miles M.2F Hawk Major |

ZK-ADJ | 2 |

|

Mad Mac McGregor | .jpg) |

Johnnie Walker | 5th in Handicap | |

|

Boeing 247D 'Warner Bros. Comet' |

NR257Y | 5 |  |

Roscoe Turner |  |

Clyde Pangborn |

Reeder Nichols (radio operator) |

3rd in Speed Race |

|

Pander S4 'Panderjager' |

PH-OST | 6 |  |

Gerrit Geijsendorpher |  |

Dick Asjes | Retired Allahabad, north-east India | |

|

Desoutter Mk II |

OY-DOD | 7 |  |

Michael Hansen |

Daniel Jensen (flight engineer) |

7th in Handicap Race | ||

|

Airspeed AS.5 Courier |

G-ACJL / VH-UUF | 14 |  |

David Stodart |  |

Kenneth Stodart | 4th in Handicap Race | |

|

Fairey IIIF 'Time and Chance' |

G-AABY / VH-UTT | 15 |  |

Cyril Davies |  |

C N Hill | Disqualified - arrived too late | |

|

D.H.80 Puss Moth 'My Hildegarde' |

VH-UQO / G-AEEB | 16 |  |

Jimmy Melrose | 3rd in Handicap Race | |||

|

D.H. Comet |

G-ACSR / F-ANPY | 19 |  |

Owen Cathcart Jones |  |

Ken Waller | 4th in Speed Race | |

|

Miles M.3 Falcon |

G-ACTM | 31 |  |

Harold Brook |

Miss Ella Lay |

Disqualified - arrived too late | ||

|

Lambert Monocoupe 110 'Baby Ruth' |

NC-501W | 33 |  |

Jack Wright |  |

John Polando | Retired at Calcutta - engine trouble | |

|

D.H Comet 'Grosvenor House' |

G-ACSS / K5084 | 34 |  |

C.W.A. Scott |  |

Tom Campbell Black | 1st in Speed and Handicap Races | |

|

Fairey Fox I |

G-ACXO / J7950, VH-UTR | 35 |  |

Ray Parer |  |

Godfrey Hemsworth | Disqualified - arrived too late | |

|

Lockheed 5C Vega 'Puck' |

G-ABGK / NC372E? G-ABFE VH-UVK A42-1 |

36 |  |

Jimmy Woods |  |

Don Bennett | Retired at Aleppo, Syria - gear trouble | |

|

Douglas DC-2 'Uiver' |

PH-AJU | 44 |  |

Koene Dirk Parmentier |  |

Jan Johannes Moll |

Bouwe Prins (flight engineer) Cornelius v. Brugge (radio operator) Roelof.Dominie P. M. J. Gilissen Thea Rasche |

2nd in Speed and Handicap Rac |

|

Granville R-6H Gee Bee 'QED' |

NX14307 | 46 |  |

Jackie Cochran |  |

Leland Smith | Retired at Bucharest, Romania - flap trouble | |

|

Klemm B.K.1 Eagle |

G-ACVU | 47 |  |

Geoffrey Shaw | Retired at Bushire, Persia - gear trouble | |||

|

Airspeed AS8 Viceroy |

G-ACMU | 58 |  |

Neville Stack |  |

Sydney Turner |

Butch McArthur (radio operator) |

Retired at Athens - electrical trouble |

|

D.H. Dragon Rapide 'Tainui' |

ZK-ACO | 60 |  |

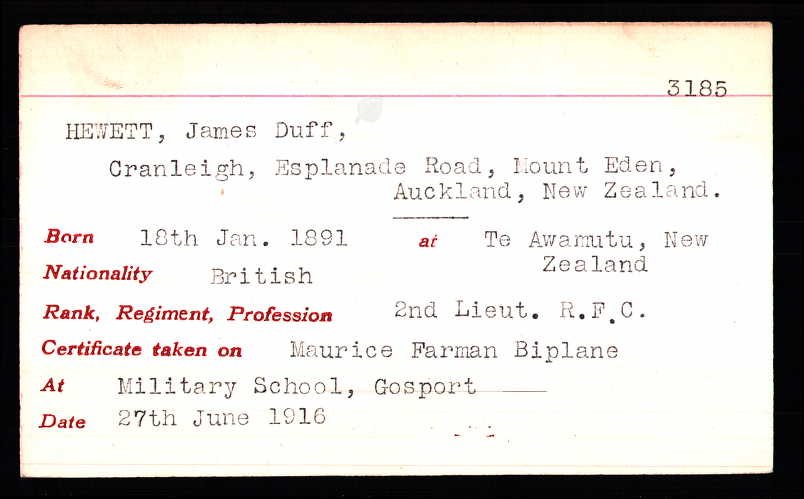

James Duff Hewett |  |

Cyril Kay |

F Stewart |

6th in Handicap Race |

|

Fairey Fox I |

G-ACXX / J8424 | 62 |  |

James Baines |  |

Harold Gilman | Crashed Foggia, Italy, killing Baines and Gilman | |

|

D.H. 88 Comet 'Black Magic' |

G-ACSP / CS-AAJ | 63 |  |

Jim Mollison |  |

Amy Mollison | Retired Allahabad, NE India - broken oil line | |

Macrobertson Race - 1934

- Click on aviator's name for full biography

-

MacRobertson Race 1934

The MacRobertson Race from Mildenhall to Melbourne 1934

The Story of the Race, at a glance:

-

- Arithmetic

For two quite separate reasons, the results of the Handicap Race (and therefore the Speed Race) were wrong!

Let me explain:Nine aircraft completed the course in the allowed time, seven of which had been entered for the Handicap Section: There were five prizes to be awarded at the end of the race:

There were five prizes to be awarded at the end of the race:Speed Race

- First Prize - £10,000 and the MacRobertson Trophy (which went to Scott and Campbell Black)

- Second - £1,500 (Turner and Pangborn in the Boeing 247)

- Third - £500 (Cathcart Jones and Waller)

Handicap Race- First Prize - £2,000 (Parmentier and Moll, DC-2)

- Second - £1,000 (Jimmy Melrose, Puss Moth)

The prizes for the Speed Race were simply based on the elapsed time taken to reach Melbourne from Mildenhall; here, Scott and Campbell Black’s Comet was the clear winner.The prizes for the Handicap Race, however, were awarded based on how well each aircraft did against its ‘handicap speed’, which was worked out by using a formula:[Handicap Speed = 140 (1-(0.2L/(W-L))) (P/A)1/3where L is the payload, W the all-up weight, P the rated power of the engines, and A the wing area.]The formula was an attempt (presumably because no time was available to establish the actual speeds) of how fast each aeroplane should be able to fly, so that a handicap time could be applied to the actual flying time to give a ‘net’ time.There are two problems with this:1 - In two important cases, they worked it out wrong, but in any case2 - The formula doesn't work, and they should have used real numbersWhich, together, mean that the wrong people got the (not inconsiderable) prizes. Settle down while I expand...1 - They worked out the handicaps wrong

This is really interesting, if you like numbers and stuff:

When they worked out the handicap speeds for the aeroplanes, they got 3 of them wrong.

You see, the formula they used gives a 'handicap speed' based on the four parameters W, A, L and P.

In fact, Handicap Speed =140*(1-(0.2*L)/(W-L))*((P/A)^(1/3)), where

W is the weight of the aeroplane, in pounds;

A is the Wing Area, in sq ft;

L is the Payload, in pounds - each crew member was reckoned to be about 200lb, but some of the aeroplanes carried other passengers and/or freight, and

P is the rated Power of the engine(s) at sea level, in horsepower.

Now, because I don't have the original calculations (they are presumably somewhere in the Royal Aero Club's Archives, if they still exist), I don't know what the figures for the actual weight of each aircraft and its actual payload were on the day. But I do know the figures for P and A, because the figures for the engine h.p. and the wing area are freely available.

So I set up a spreadsheet to try different (but realistic) values of the weight and the payload, to see if I could derive the same result as they did in 1934.

1 - The Desoutter

The Desoutter has a maximum take-off weight of 1900lb, its engine is 120h.p., and it has a wing area of 183 sq. ft. Using a value of 470 lb for the payload (2 people, plus a bit), it has no problem coming in at the 'right' figure of 113 mph:

and neither does 2 - The Puss Moth

... and so on, through 3 - the Klemm

4 - The Miles Falcon:

5 - The Hawk:

and 6 - the Dragon Rapide (although the payload seems a bit high):

(Still with me?)

However, the chart for 7 - the Courier comes out funny:

This means...

There are no possible values for the weight of the aircraft, and the payload it carried, which would give us 140.53 m.p.h. as the Handicap Speed.

What can possibly have happened?

I think the answer is quite simple, actually - if you plug in 270h.p. as the power of the engine, hey presto:

Now, if you remember your Airspeed Courier facts, there were two versions. One (the version the Stodarts intended to fly, and registered for the race) had a 270hp Cheetah engine. The other (the version they actually flew) had a 240hp engine.

... their handicap speed should have been about 135mph, not 140mph.

Better check out the rest of them, I suppose:

8 - the Fox looks OK:

9 - The Comet is OK, too (that's a relief):

and so is 10 - the Fairey IIIF:

and even 11 - The Lambert Monocoupe squeezes in (wing area looks a bit suspect, but...)

but what have we here... 12 - the DC-2 is wrong, as well:

Working back from the result, they must have assumed the DC-2 would have a total of 1750 hp (which it certainly didn't):

... the DC-2 should have had a handicap speed of about 159mph, not 168mph.

Nearly there, thank goodness...

13 - the Vega looks fine:

but poor old 14 - the Airspeed Viceroy was hard done by, too:

They must have assumed it would have 712hp:

Oh well... it didn't finish anyway. :-)

All of which means that...

The Courier, instead of a handicap time of 87:36:59, should have had 91:14:52.

The DC-2 should have had 77:01:34 rather than 73:16:56

The Courier spent 100:24:06 hrs completing the race - 9:09:14 hrs more than its proper handicap time.

The DC-2 only took 83:09:24hrs - 5:52:28 hrs more than its real handicap time.

However, Jimmy Melrose (who got the second prize originally), took 120:16:02, which was 12:34:19 over his handicap time.

So, actually, after all that, if they'd done the arithmetic properly, the Stodarts should have had the runners-up prize, instead of Jimmy (despite what Kenneth said after the race about it being a 'pity to do him out of the second prize'!)

2 - It gets worse - they used the wrong speeds anyway

Unfortunately, the results of the formula turned out to be a rather poor predictor of the maximum speeds of the aircraft involved. The comparative figures for the seven finishers in the handicap section are shown below: Flight (October 25th, 1934) noted that“No one has yet succeeded in evolving a formula which is fair to all types of aeroplane for purposes of handicapping, and the formula used in the England-Australia race is no exception.”“It is, perhaps, doubtful if any other machine in the race ‘beats’ the formula by such a wide margin as that of the ‘Comets’ (about 50 m.p.h.) But it is worth remembering, in this connection, that the ‘Comets’ were specially designed for the race, and were, in fact, the only machines to have this distinction. To achieve a speed of more than 230 m.p.h. when carrying two people and enough fuel for a flight of 2,500 miles (with a fair margin for head winds) with engines totalling but 460 h.p. is a performance which no formula based upon average values could be expected to cope with.”Before the race began, more doubts were being expressed about the reliability of the formula:“The handicaps have just been announced and as [Stack in the Airspeed Viceroy] is scratch man in the handicap race and is set to give a start to several machines which are known to be faster, it appears that [his] luck is out”“...the poor old Fairey IIIF which has been handicapped to do a speed of nearly 150mph, at least 20mph more than it can hope to accomplish...”Alan Goodfellow, Clerk of the CourseUsing the handicap speeds derived from the formula, the final results for the Handicap Section were:

Flight (October 25th, 1934) noted that“No one has yet succeeded in evolving a formula which is fair to all types of aeroplane for purposes of handicapping, and the formula used in the England-Australia race is no exception.”“It is, perhaps, doubtful if any other machine in the race ‘beats’ the formula by such a wide margin as that of the ‘Comets’ (about 50 m.p.h.) But it is worth remembering, in this connection, that the ‘Comets’ were specially designed for the race, and were, in fact, the only machines to have this distinction. To achieve a speed of more than 230 m.p.h. when carrying two people and enough fuel for a flight of 2,500 miles (with a fair margin for head winds) with engines totalling but 460 h.p. is a performance which no formula based upon average values could be expected to cope with.”Before the race began, more doubts were being expressed about the reliability of the formula:“The handicaps have just been announced and as [Stack in the Airspeed Viceroy] is scratch man in the handicap race and is set to give a start to several machines which are known to be faster, it appears that [his] luck is out”“...the poor old Fairey IIIF which has been handicapped to do a speed of nearly 150mph, at least 20mph more than it can hope to accomplish...”Alan Goodfellow, Clerk of the CourseUsing the handicap speeds derived from the formula, the final results for the Handicap Section were: Under the Race Rules, the Comet had to choose between the speed prize and the handicap prize and not surprisingly chose the former. The DC-2 was declared the winner of the handicap section, with Jimmy Melrose in the Puss Moth in second place.However, if they had used the published maximum speeds quoted above to establish the net time, the results would have looked rather different:

Under the Race Rules, the Comet had to choose between the speed prize and the handicap prize and not surprisingly chose the former. The DC-2 was declared the winner of the handicap section, with Jimmy Melrose in the Puss Moth in second place.However, if they had used the published maximum speeds quoted above to establish the net time, the results would have looked rather different: All of which leads to these conclusions:1 - Scott and Campbell Black still win. Congratulations to them.2 - The DC-2, instead of winning the Handicap Section, should have gone for second prize in the Speed Section.3 - The inadequacies of the handicappers’ formula robbed the Stodarts of their place on the winners’ podium!Of course, those maximum speeds cannot now be corroborated exactly; the way to remove any doubt would have been (as is done for modern race handicapping) to run a series of check flights under controlled conditions to determine the actual speed. In addition, a difference of a few m.p.h. here or there would make a significant difference to the end result.The Stodarts lodged a protest but this was to do with inaccurate checking times, and was not upheld.“When told that the protest had been dismissed, Mr. [Kenneth] Stodart did not appear to be particularly surprised. He said that the independent stewards appointed to adjudicate had nothing tangible to work on, and had had to rely on the times given by officials at overseas aerodromes. 'And Melrose is a splendid fellow,' Mr. Stodart added. 'It would have been a pity to do him out of second place.' “The West Australian, 22 NovemberAll of which means that my totally unofficial results are:Speed Race

All of which leads to these conclusions:1 - Scott and Campbell Black still win. Congratulations to them.2 - The DC-2, instead of winning the Handicap Section, should have gone for second prize in the Speed Section.3 - The inadequacies of the handicappers’ formula robbed the Stodarts of their place on the winners’ podium!Of course, those maximum speeds cannot now be corroborated exactly; the way to remove any doubt would have been (as is done for modern race handicapping) to run a series of check flights under controlled conditions to determine the actual speed. In addition, a difference of a few m.p.h. here or there would make a significant difference to the end result.The Stodarts lodged a protest but this was to do with inaccurate checking times, and was not upheld.“When told that the protest had been dismissed, Mr. [Kenneth] Stodart did not appear to be particularly surprised. He said that the independent stewards appointed to adjudicate had nothing tangible to work on, and had had to rely on the times given by officials at overseas aerodromes. 'And Melrose is a splendid fellow,' Mr. Stodart added. 'It would have been a pity to do him out of second place.' “The West Australian, 22 NovemberAll of which means that my totally unofficial results are:Speed Race- First Prize - £10,000 and the MacRobertson Trophy (Scott and Campbell Black)

- Second - £1,500 (Parmentier and Moll, DC-2)

- Third - £500 (Turner and Pangborn, Boeing 247)

Handicap Race- First Prize - £2,000 (David and Kenneth Stodart, Airspeed Courier)

- Second - £1,000 (Jimmy Melrose, Puss Moth)

Sorry, Cathcart Jones and Waller... -

-The Aviators

The Aviators

-

Asjes, Dirk Lucas

Dirk "Dick" Lucas Asjes

Born 21st June 1911 in Surabaya

Born 21st June 1911 in SurabayaDied 2nd February, 1997 in the Hague, aged 85

-

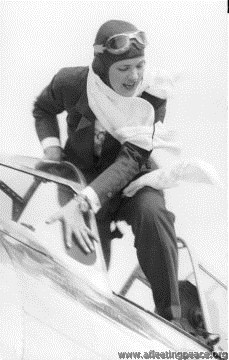

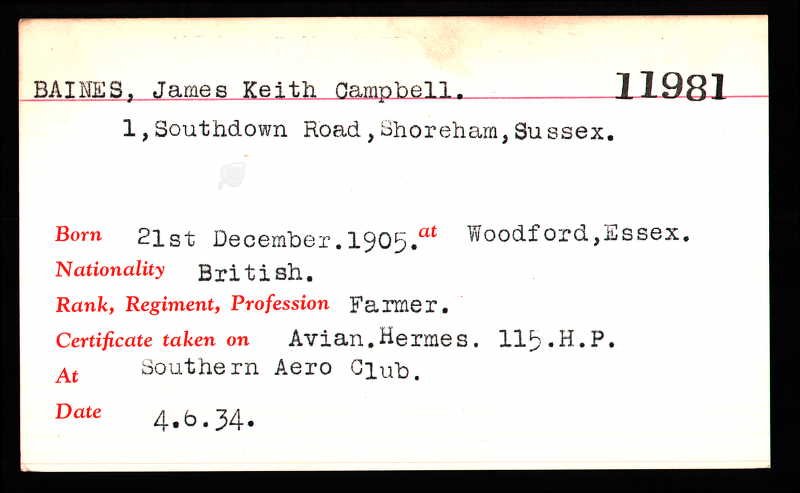

Baines, James Keith Campbell

James Keith Campbell Baines

Born 21st December 1905 in Woodford, Essex. His father, Louis, was a tea and indigo merchant; his elder sister Phillis was born in Calcutta. In 1901 the family lived in Tiverton, Devon; Louis, Lillian, Phillis, Jack, Silsen, Kathleen, and their 3 domestic servants.

He was killed, aged 28, during the MacRobertson Race on 23rd October 1934 when he and Gilman crashed in Italy.

Joined the N.Z.A.F. in 1925, training at Palmerston North and Wairapa.

He arrived in London from New Zealand on March 26, 1934. He sold his Avro "Avian," just before departure, to a brother-officer in the N.Z.A.F. Reserve, and embarked for England in January, via Australia and South Africa. During the ship's stay in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth and Capetown, Baines kept his hand in with flights on machines hired from the local aero clubs. At the time of the Race, he had flown 3,860 hr.

His "Fox" was purchased at Hounslow from Anderson Aircraft and was modified at Hanworth by N.F.S., Ltd., as a replica of the sister-machine entered by Raymond Parer. Its capacity was increased to 175 galls., and its range to about 1,750 miles.

"Whilst awaiting delivery of the "Fox," Baines has been making approach landings at Mildenhall. He expresses himself delighted with the new aerodrome, its freedom from obstruction, its perfect run, and its billiard-table surface."

-------

In July, 1934, James wrote to the organising committee for the race and asked them to 'change the name of the nominator from myself to Mrs Lilian M Campbell-Baines, my mother, who has made it possible for me to enter the Races'.

Baines and Gilman crashed on the 10th of October 1934, and the funeral, at the British Cemetery at Naples, was held on the 26th. The British Air Attache in Rome, Group Captain T Hetherington, undertook all the funeral arrangements; the photographs of the ceremony 'very clearly indicated the profound sympathy of the Italian nation and the honours bestowed on these two officers'.

Sadly, James' brother had also been killed earlier in the year in a gun accident; their eldest brother had been killed during WWI also flying, aged only 19.

Although they had insured the aeroplane, Baines and Gilman hadn't taken out any life insurance.

-

Bennett, Donald Clifford Tyndall

Donald Clifford Tyndall Bennett CB CBE DSO RAF

b. 14 September 1910 in Queensland

b. 14 September 1910 in QueenslandWith Imperial Airways, promoted to Senior Master in October 1938

'Pathfinder' Bennett for his work with Bomber Command during WWII. As you probably know, the Pathfinder Force consisted of people who actually knew how to navigate properly, and marked the targets for the bombers.

In May 1945, he became a Liberal M.P.: "Air Vice-Marshal D. C. Bennett, Pathfinder chief and youngest man of his rank in the R.A.F., was returned unopposed to-day as Liberal M.P. for Middlesbrough West."

In 1948 he and his wife bought a couple of transport aircraft, formed AirFlight Ltd, and joined the Berlin airlift to fly dehydrated potatoes to the 2 million population.

CEO of British South American Airways until forced to resign over an interview he gave in 1948.

Opinions varied on what had happened: "SACKED FOR SPEAKING MY MIND-Airway Chief Air Vice-Marshal D. C. T. Bennett has been dismissed from his post as chief executive officer of British South American Airways. The following statement was issued by the British South American Airways Corporation: "The board have terminated the appointment of their chief executive, Air Vice-Marshal D. C. T. Bennett, following differences of opinion on matters of policy.

In a statement, Air Vice-Marshal Bennett said:— "Last week, in view of current misinformation on certain affairs of this corporation, I granted an interview to a newspaper correspondent, at which I expressed views concerning the obvious ills of British civil aviation in general and concerning recent interference with management by the Minister of Civil Aviation. It is because of this that I have been forced to discontinue my appointment. I feel I should make it clear that I have been forced to take this course for exercising what I consider to be a right—the freedom of speech."

"A personally difficult and naturally aloof man, he earned a great deal of respect from his crews but little affection."

He also came 8th in the Monte Carlo Rally of 1953, driving a Jaguar.

Wrote his autobiography in 1958, called, of course, 'Pathfinder'.

Died 15th September 1986, aged 76

-

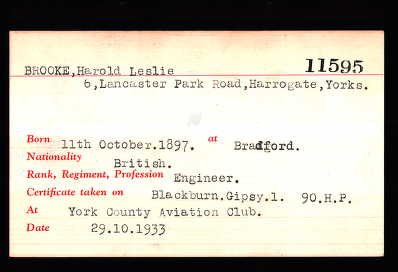

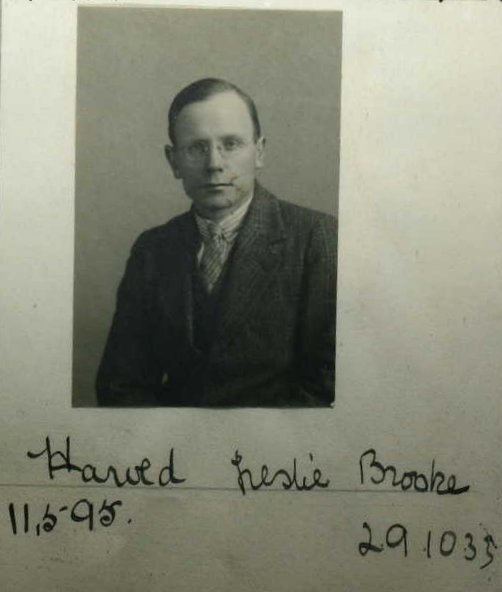

Brook, Harold Leslie

Harold Leslie Brook

b. 11 October 1897, in Bradford

Only learnt to fly in 1933, and just scraped up the minimum 100hrs solo flying time required to enter the Race. The aircraft was barely ready in time either; a month before the start it didn't have any seats, and was in "a very unfinished condition". Harold was not impressed by "those fools at Reading [i.e. Miles Aircraft]... this is not the first time they have omitted to do something".

In March 1934, he tried to break the England-Australia solo record (held by CWA Scott) but only got as far as the Cevennes before crashing into one of the large mountains they have there. To give him his due, he picked up the important bits of his aeroplane, brought them back and used the engine in this Miles Falcon.

In 1935, after taking part in the MacRobertson, he flew back from Australia in record time; you might like to see him talk about his record-breaking flight (on the other hand, you may have some drying paint that needs watching); if so, click Record Flight From Australia - British Pathé (britishpathe.com)

Two years later, he added the Cape Town record. Mercifully, there don't appear to be any interviews about this one.

Pilot Officer in the Administrative and Special Duties Branch in May 1940, then briefly (28 Oct 1940 - 3 May 1941) in the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA)

And, despite what you may read or hear, was never an accountant in his life (although with his spectacles on, he did rather look like one, and when he talked, he did rather sound like one [sorry]), and he signed himself 'Brook', not 'Brooke'.

But 'e were definitely from 'Arrogate.

H. L. BROOK writes to TERRY'S

Dear Sirs,

I should like to take this opportunity of congratulating you on the excellence of your Springs in my Gipsy 6 Engine. In a record-breaking flight of this description the engine has to be run for long periods in extreme temperatures, and at a higher rate of revolutions than normal, and for a valve spring to break would spell disaster. I had never at any time any fear of this happening with your springs, and they are now at the end of the flight in just as good condition as they were at the start.

Yours faithfully,

(signed) H. L BROOK.

'Flight'

Racing No. 31—H. L. Brook, and —?

And speaking of Bradford, here is Harold Leslie Brook, who was born there in 1897, and now resides in Harrogate. He joined the Royal Field Artillery on August 20, 1914, at the age of 16, obtained his commission soon afterwards, and, despite a couple of wounds, served five years in France and India.

Restored to his family, he remained a normal civilian until Yorkshire began to build and fly sailplanes and gliders. These occupations kept him mildly diverted until the approach of his 37th birthday. Then he began to yearn for horse-power. The York County Aviation Club at Sherburn-in-Elmet offered a likely fulfilment of this secret ambition. So, in August, 1933, Brook placed himself in the hands of Instructor Cudemore, and after four hours' instruction became a soloist with serious designs on the MacRobertson Handicap, for which Phillips and Powis have built him the first of their Miles 'Falcons'.

What happened between last autumn and this spring is now almost historic. Brook bought the "Puss Moth" (Heart's Content) in which the Mollisons had crossed the Atlantic, and, with a total of 43 hr. in his logbook, pushed off solo from Lympne to survey the route to Melbourne. That was on March 28, 1934, at 5.20 a.m.

By noon the incident had closed. Describing it a few days later Brook said that, while flying through very dirty weather over France, he was forced down from 12,000 ft. by ice formation on the wings, and, before he knew how or why, the side of an unsuspected mountain was rushing up at him out of the murk. Guided by some uncanny sixth sense, he brought off a bloodless landing on the mountain proper. The scene of this epic of the air was Genolhac, in the Cevennes. With some local help he salvaged the "Gipsy Major," brought it back to England, and has had it installed in Heart's Content II.

Brook's next attempt on the Australian record will not be solo. If expectations are realised, he will be accompanied by two lady passengers.

'Flight'

Another England-Australia attempt

MR. H. L. BROOKE, a member of the York County Aviation Club, left Lympne at dawn on the morning of Wednesday, March 28, on an attempt to break the record for the England-Australia trip held by Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith with the time of 7 days 3 hours. Mr.Brooke was flying the " Puss Moth " (" Gipsy III ") Heart's Content, in which Mr. J. A. Mollison made an Atlantic crossing. A few hours after leaving Lympne, while flying through fog, he crashed in deep snow near Genholac, in the Cevennes. The machine was completely wrecked, but Mr. Brooke escaped with nothing worse than some bad bruises. For five hours he wandered about inthe mountains, and eventually found a small village, where he was given every attention. Later he returned to the wreck of his machine, and removed the instruments and other articles of value.

'Flight'

April 4, 1935

YORK COUNTY AVIATION CLUB, SHADWELL, LEEDS

During March the York County Aviation Club, Ltd., flew 63 hours at Sherburn-in-Elmet, and Miss Maurice and Mr.Pilkington made first solos. Two machines flew to Nottingham for the club dance, and Mr. Humble, the honorary instructor, has presented the club with a fire tender—a very apposite gift! The next dance will be held on April 13.

Mr. H. L Brook, who has just broken the Australia-England record with a Miles " Falcon," was trained at Sherburn—which appears to be a pretty good advertisement for the instruction.

'Flight'

These days, the home of Sherburn Aero Club: http://www.sherburn-aero-club.org.uk/

SWIFTLY from AUSTRALIA

How H. L. Brook, in a " Gipsy "-engined Miles "Falcon" broke the Solo Record : His Story in an Interview with " Flight

"LAST Sunday afternoon, at 3.55 p.m., the original Miles" Falcon " landed at Lympne, having flown in 7 days•* 19 hr. 50 min. from Darwin, North Australia, withMr. H. L. Brook, of Harrogate, at the controls. The •pilot thus beat the unofficial " s o l o " record of Mr. C. J.Melrose by 13 hr. 10 min., and the officially recognisedperformance of Mr. J. A. Mollison by 1 day 2 hr. 25 min.The shortest time for the Australia-England trip is still,of course, the 6 days 16 hr. 10 min. of Cathcart Jones andWaller in a " C o m e t ."After leaving Darwin at 5.30 a.m. on Sunday, March 24(Australian time), Mr. Brook's time-table was as follows:—Sunday night, arrived Rambang ; Monday, Penang; Tuesday,Rangoon; Wednesday, Calcutta; Thursday, Karachi; Friday,Athens; Saturday, Rome; Sunday, Marseilles (9.25 a.m.) ;Lympne (3.55 p.m.).the Timor crossing, he told a member of the staff of Flight,was " r o t t e n , " with rain, low clouds and heavy head winds.On the trip from Penang he landed on the delta near Calcutta.Over the Sundarbans low clouds and darkness caused him totake this measure rather than to fly on, possibly missingCalcutta, and, as he put it, perhaps making a crash landingthrough shortage of petrol.Perhaps the worst section of the trip was that betweenAthens and Rome, particularly the portion over the channelof Corfu, where a gale was encountered. At Brindisi Mr.Brook was advised not to proceed, but he pushed on andcrossed the Apennines in a snowstorm.And what of the man himself? He is a thirty-eight-yearoldYorkshireman, who, despite the newspaper stories, hasnever been an accountant in his life. When he was youngerhe indulged in motor racing and later built a few sailplanesand gliders. Then he joined the York County Aviation Cluband went solo after four hours' instruction. He next boughtMr. J. A. Mollison's "Puss Moth" Heart's Content, and setout for Australia to survey the route to Melbourne, for he haddecided to enter the MacRobertson Handicap. But ice formationforced the " Puss Moth " down on a mountain side inthe Cevennes. Neither Brook nor the "Major" (which, itshould be remembered, had already been flown over the SouthAtlantic) was rendered hors de combat, however. The enginewas salvaged and Brook brought it back to England, where itwas installed in the first of the Miles " Falcons" which thenwas fitted with extra tanks for the race. During the event itcarried a lady passenger and a large helping of appalling

luck (no connection is suggested between the two facts!).Suffice it to say that the Australian trip, a large portion ofwhich was made in easy stages, took about twenty-six daysDuring his stay "down under," Brook worked until the" F a l c o n " and its engine were in tip-top condition beforestarting his almost unheralded flight.Of travelling in the "Falcon " he says that, compared withflying in an ordinary aeroplane with open cockpits, it was" like travelling in a saloon car instead of on a motor cycle. The veteran "Gipsy Major" was run throughout the flight at 2,100 r.p.m.

HILLSON PRAGA

Imported specimen 107 Praga E.114 OK-PGC. Regd G-ADXL (CofR 6479) 27.11.35 to F Hills & Son Ltd; dd Speke to Barton 30.12.35. CofV 91 issued wef 27.2.36. Dd 20.4.36 to Harold Leslie Brook; flown by him to South Africa, departing England 6.5.36; arriving Cape Town 22.5.36. Regn cld 6.36 as sold. Regd ZS-AHL 6.36 to OG Davies, Cape Town. Sold 8.37 to H Cooper, Cape Town. Converted to glider at Youngsfield 9.53.

30th Aug. 1940.

ADMINISTRATIVE AND SPECIAL DUTIES BRANCH.

The undermentioned are granted commissions for the duration of hostilities as Pilot Officers on probation:— 22nd May 1940.Harold Leslie BROOKE, D.C.M. (84353).

-

Campbell Black, Tom

-

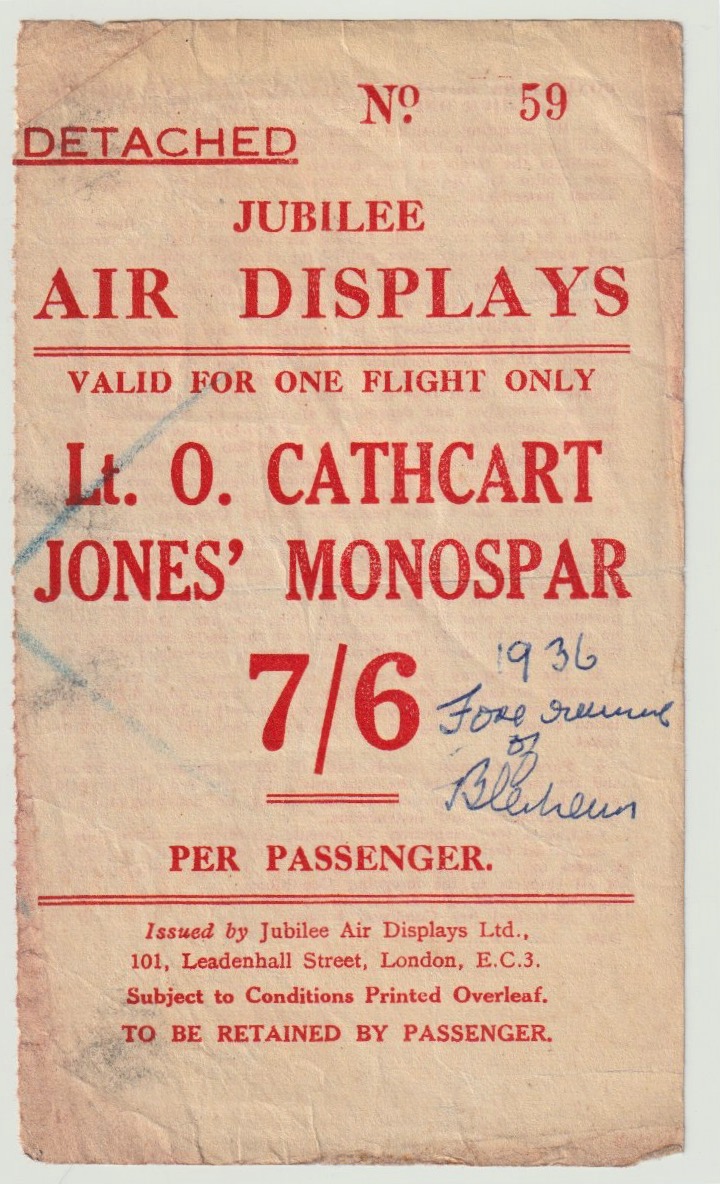

Cathcart Jones, Owen

Lt Owen Cathcart Jones

1934

1934 Born 5th June, 1900, London (definitely not Canadian, despite some nasty rumours).

McRobertson Centenary Gold Medal 1934

Royal Aero Club Silver Medal 1934

Holder of 8 Long Distance World Records. 1934

It's difficult to know what to make of Owen Cathcart-Jones, really; he was handsome, adventurous, undoubtedly talented, and clearly an excellent aviator - but, I'm afraid, rather prone to go 'AWOL' - both in his personal and service life!Born in London on 5 June 1900, he joined the Royal Marines in 1919, then, after the usual period of general service he volunteered for flying and joined R.A.F Netheravon on 12 January 1925, in the first batch of Marines officers to be transferred.

He was awarded his 'wings' in August 1925 and was posted to RAF Leuchars, serving with 403 Flight on HMS Hermes, and 404 Flight on HMS Courageous, taking a hand in the troubles in China in 1926-27 and again in Palestine in the following year.

In 1927, he wrote to The Times:

Sir,

On July 17 I had occasion to be flying down the east coast of Greece, and when in the vicinity of Mount Kissavos, near Larisa, I was astonished to see a large golden eagle fly past my aeroplane on a parallel course at a distance of about 80 feet away. The bird did not appear to be at all concerned at the noise of the engine, and in fact turned its head round to look at the aJrcraft on passing. The speed on my indicator showed 70 knots, and the height by my altimeter was 4,000 feet. Judglng by the speed at which I was passed by this bird, I should estimate that it must have been travelling at 90 mp.h.; which I consider to be quite a phenomenal speed for such a large bird at that high altitude.

Yours faithfully,

OWEN CATHCART-JONES,

Lieut. H.M.S. Courageous, at Skiathos, Greece, July 22.

which prompted Mr Seton Gordon, from the Isle of Skye, to reply:

Sir,

The letter from Lieutenant Owen Cathcart-Jones in The Times of July 27 which describes the great speed of a golden eagle in flight is of interest to me, as I have for some time believed the eagle to be one of the fastest birds. On one occasion I satisfied myself that an eagle was travelling at a good 120 miles an hour - probably much more -but then the bird was rushing earthward from a considerable height, and Lieutenant Owen Cathcart-Jones's bird was apparently on a level course. Little is definitely known even to-day as to the maximum speed any bird is capable of. Not so long ago a senior officer of H.M.S. Hood told us that when the Hood was steaming 34 miles an hour into a 15-mile-an-hour wind a formation of guillemots had no difficulty in forging ahead and crossing the vessel's bows. This interesting record shows that even the humble guillemot is capable of an air speed of well over 50 miles an hour, so a speed of 90 m.p.h. is not surprising in a bird of the wing power of a golden eagle.

I am, &c.,

During this time, he met Audrey, the wife of Captain Hugh Fitzherbert Bloxham, late of the Indian Army, then a Colonial Office official in the Prison Department at Hong Kong. Hugh and Audrey had married in St John's Cathedral, Hong Kong, on 6 August 1925.

Clearly Owen and Audrey got along rather well, and in November, 1927, their daughter Imogen was born.

Hugh duly sued Audrey for divorce in May 1928, "on the ground of her adultery, at the Hotel Savoy, Hong Kong, with Lieutenant Owen Cathcart-Jones, of the Royal Marines." The petition was uncontested.

On 12 Aug 1929 in Malta, Audrey had a son, Anthony.

"He established a reputation as a forceful and daring pilot, and one of his escapades became the talk of the Fleet; on 22 Aug 1929 he was on exercises with the Fleet and loaded his plane with a large packet of "service brown" toilet paper intending to drop it on H.M.S. Revenge which should have been last in the line. Unfortunately the C-in-C had inverted the line and he dropped the "bumph" very accurately on the Flagship, H.M.S. Queen Elizabeth. His Flycatcher aircraft was clearly numbered "7" and the Captain of H.M.S. Courageous was called to the Flagship on return to harbour to explain. Cathcart-Jones duly appeared before the Admiral with his reasons in writing [he made up some nonsense about it acting as a 'sighter' for actual bombs] and had to be on his best behaviour for some time."

On 26 November 1929 he made the first ever night deck landing in a fighter aircraft, flying a Fairey Flycatcher from H.M.S Courageous.

"It is a reminder of our one time presence in the Middle East that his record shows his Flight carrying out patrols in Palestine, and the Courageous Flights being shore based at Gaza and Aboukir in 1929 during the 'Civil War'.

During his Fleet Air Arm service he became very friendly with a wealthy Naval Officer, Glen Kidston, with a similar passion for flying. Kidston was himself leaving the Navy and Cathcart-Jones decided that it was time to do likewise and to transfer his interests entirely to civil flying. He went on to half pay on 17 Febuary 1930 [for 6 months], joined National Flying Services Ltd. and never returned to the Service.

Audrey, by then aged 28, with Imogen (aged 2) and Anthony (aged 1) sailed from Brisbane to Plymouth on the P&O steamship Ballarat, arriving there on 21 Jan 1930.

On 21 April 1930, National Flying Services held their first display at Hanworth Park; Owen provided the finale by bombing a level crossing to bits. However, the meeting was not a success; "for some reason N.F.S. shows do not appeal to the average private owner" and crowds were poor.

In September 1931 he flew a D.H. Puss Moth, with Audrey as passenger, in the Deauville-Cannes Air Rally. After lunch and a gala dinner, they flew on to Cannes, despite a forced landing in the Alps when the fuel pipe and filter were found to be blocked with sand.

By the following May (1932), business was better; "taxi work is now on the increase and the N.F.S. pilots have been kept busy flying to places as widely separated as Plymouth and Berlin". Owen piloted G-ABTZ, a Stinson Junior belonging to Mr. E James, on several flights. On 31 July 1932, Audrey went on a conducted tour organised by NFS, of "eight Moths, one Bluebird and one Alfa Romeo", to Ostend.

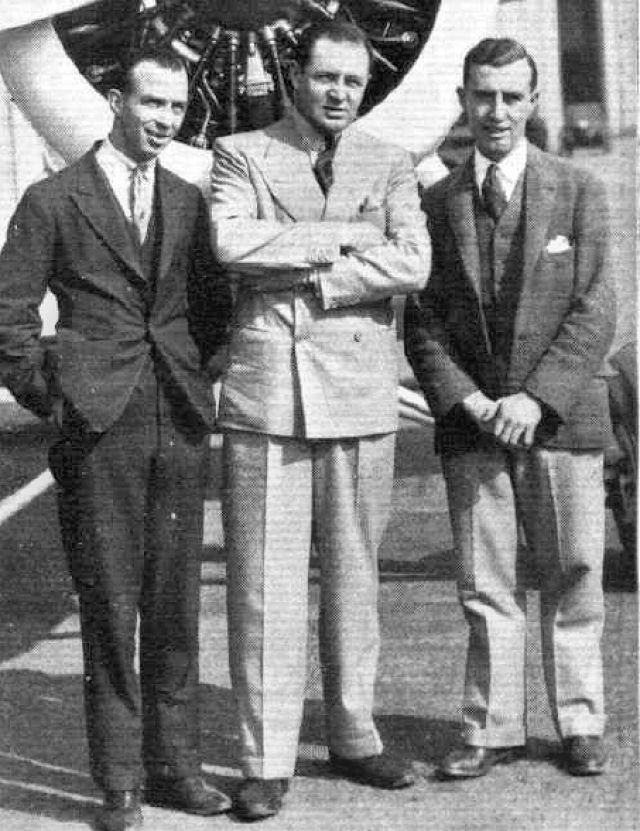

Owen and Audrey lived in Tudor Court, Hanworth, London until 1934, but then Owen moved out, leaving her and the two children, who relocated to Wavenden, Bucks. In company with Kidston he broke 8 World records for long distance flights in 1934, including England to South Africa in a Lockheed Vega:

but Glen (centre) was killed in an air crash shortly afterwards.

Owen also came 6th in the 2nd Morning Post Cross-country Air Race on 6 June 1933, and competed in the King's Cup in 1934 (finishing 9th) and 1935 (when he came a creditable 3rd).

Here he is, wandering around waiting to take-off, and taking a pylon in the final of the King's Cup 1934:

His real moment of glory was to co-pilot with Ken Waller the specially built D.H. Comet in the 1934 McRobertson England to Australia Centenary air race, in which they were awarded third prize in the Speed Handicap. On arrival they immediately turned round and flew back to England and established a record for the round trip.

Originally, he had teamed up with Miss Marsinah Neison in a Lockheed Altair (or Vega), "placed at their disposal by the builders", or possibly a Northrop Delta. However, nothing came of this.

He certainly wasn't first choice as Comet pilot - Bernard Rubin, the owner and intended pilot of the aeroplane, fell ill and originally nominated as substitute Mr Smirnoff 'the well-known Dutch pilot' on October 1st, and then only on October 5th (2 weeks before the race) 'finally and irrevocably' decided it should be Owen who accompanied Ken Waller. Three weeks before the Race, Owen had "never heard of Mr Rubin or Mr Waller", but apparently Marsinah said "Seajay, why don't you try and take Rubin's place?" Owen considered this a "most sporting action" on her part, but this meant that he had very little time to familiarise himself with the notoriously-tricky aeroplane.

After the return trip from Australia, Owen said "We have averaged 10 hours' flying every day, and covered approximately 2,200 miles a day. We wanted to make this flight back not so much as a speed flight, but as a flight which could be copied for commercial purposes. We have flown only by day, and have had time to sleep, eat, and wash. From the commercial point of view I think there is no reason why there should not be a service between Melbourne and England on similar times to those we have taken, certainly for the carrying of mails.

People in the Colonies were very anxious to have their letters quickly and to have air-mail services covering the distance in so short a time. We had one nasty moment at Allahabad, when we had trouble with two of the cylinders, but the Mollisons came to the rescue and lent us spare parts - a very sporting action. We were greatly disappointed by the delay at Athens owing to bad weather conditions, which prevented us from getting to Lympne yesterday."

Messages of congratulations included this one: "The Duke of Gloucester directs me to congratulate you both on a magnificent double flight - Private Secretary, Duke of Gloucester.

However, even while he was away, the law was after him: "ENGLAND-AUSTRALIA AIR PILOT SUMMONED. Flight Lieutenant Owen Cathcart Jones, of the Naval and Military Club, Piccadilly. who is taking part in the air race to Australia, was summoned at Bow Street Court yesterday, on a charge of using a motor-car with an expired Road Fund licence. He did not appear, and on being informed that Lieutenant Jones was one of the competitors in the England-Australia race, Mr Dummett adjourned the summons sine die."

In 4 April 1935, several visitors arrived by air for the Norfolk and Norwich Annual Dinner, including " Lt. O. Cathcart-Jones and Miss M. Neison in a Puss Moth".

He published his "Aviation Memoirs" in 1935; "... breezy, light and interesting... the book is unusually well illustrated, with photographs which Mr. Cathcart Jones has collected or taken himself, and many of these photographs are extremely graphic and educative." Interestingly, Owen rather neglects to mention anything about his wife and children.

In 1935, Ken Waller got annoyed with him for something he said in this book that Ken felt "reflected on his courage and ability as a pilot", and even went to court over it. Owen replied that "that was the last thing he intended, as Mr. Waller and he had been, and still were, very good friends", which seemed to settle the matter.

Reading the memoirs, I can only assume this was the passage where, having got themselves lost in bad visibility over Arabia during the Race, Owen says that "little did I know that Ken was on the point of asking me to dive the machine into the ground and get it all over rather than face the possibility of running out of petrol, forced landing in the sand, where we certainly would have smashed the machine, and then lie there slowly dying without means of help."

In fact, Owen's is a rather bland account of their two-way trip, and at one point Owen credits Ken with a 'marvellous achievement'; "Ken, under great difficulties, made a superb landing".

Also in 1935, he drove a 4.5 litre Lagonda Rapide in the Monte Carlo Motor Rally, starting from Stavanger in Norway. He was the first competitor to arrive in Monte Carlo, and was thought to have a good chance of winning the first prize, but was eventually placed 34th. His 'second-in-command' was a Miss Marsinah Neison, "one of the very few women to hold a 'B' licence for aircraft".

Owen and Marsinah got up to quite a few things together:

Beatrice Marsinah Neison, b. 3 Dec 1912 in Reigate. She gained her RAeC certificate at National Flying Services, Hanworth on the 11 Jan 1932, and passed the night-flying test in September.

Owen says of her "a young commercial pilot came to me for some advanced flying instructions, and I was very much impressed with the exceptional ability shown by her. Miss Marsinah Neison was the youngest girl pilot to get the coveted 'B' commercial pilot's licence. She qualified for it at the age of nineteen." He reckoned "there was very little I could teach her... I decided that her abilities were far too high to waste, and asked her to join me in any free-lance air charter work in which we could combine".

I'm not suggesting anything untoward, you understand...

In November 1933, she was trying to raise finance for a solo flight to Australia in a Comper Mouse, to beat the record held at the time by CTP Ulm, but never did.

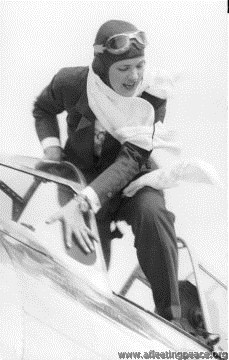

Here she is, ready to go:

She sailed to California in May 1936, to visit her friend 'Russell Pratt', (sounds like an assumed name to me...) and to New York in July 1937. She married Hart Lyman Stebbins of New York 'very quietly' in London in December 1937, (they appear in the 'New York Social Register', whatever that means, for 1941), then Angus MacKinnon in July 1947. She died 29 April 1997 in Hampshire (England).

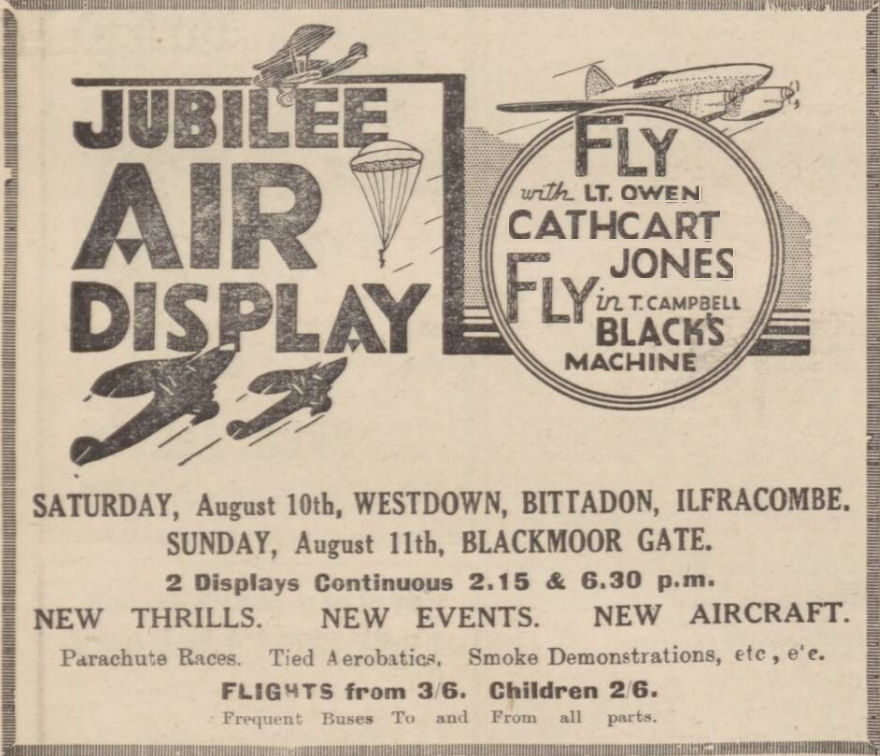

Anyway, Owen was by now pretty well-known; in May 1935, for example, he, Mrs Mollison (Amy Johnson), Tom Campbell Black, and other aviators took part in a 'Mock Trial', in aid of King Edward's Hospital Fund for London, at the London School of Economics; they were charged with 'Making the world too small'. The following August, he was chief pilot in the 'Jubilee Air Display', also with Tom Campbell Black.

via Joss Mullinger

via Joss Mullinger"Lieut. Owen Cathcart-Jones and Mr. T. Campbell Black, two of the keenest rival prize-winning pilots in the great England-Australia Air Race last year, are combining in a brilliant partnership to take a leading part in the Jubilee Air Display which will be given at Home Farm, Tehidy, Camborne, Thursday, August 15th. 2.15 till dark. The display which is visiting no fewer than 180 centres throughout Great Britain during the summer months, has been specially planned to provide a striking demonstration of the supremacy of British modern commercial aircraft and the unrivalled skill of British pilots. Public interest in aviation has never been more keen than it is at the present moment."

Don't be fooled into thinking you might have flown in the D.H. Comet, though - Owen flew passengers in a four-seat G.A.L. Monospar, and Tom took them up in an Avro Cadet, a rather pedestrian trainer.

On 31 July 1935, Owen advertised, again in The Times: "Mr Owen Cathcart-Jones requires sponsor to finance building world's fastest commercial aeroplane for nine special long-distance record flights in 1936-7 showing profitable return."

Nothing came of this either...

By December that year, however, Owen was banned from flying in Argentina because of his 'stunts'near a military aerodrome; the following April, his aeroplane was impounded by the Austrian authorities and he had to make his own way back home via Cannes.

Gigi Jakobs tells me that "I came across his name in divorce proceedings for Robin W.G. Stephens and Phyllis Gwendlen (nee Townshend) Fletcher. They started divorce proceedings in late 1936 because, according to Stephens, his wife had committed adultery with Cathcart Jones from Dec 1935 to May 1936."

26 Jan 1937

"Owen Cathcart Jones, the well-known airman, of Grosvenor Street, London, failed to appear at his first meeting of creditors at the London Bankruptcy Court to-day. The assistant official receiver stated fhat the debtor had failed to surrender under the proceedings. A distress was levied at his flat last December, and goods sold in January. A representative of the petitioning creditor said that the debtor took an aeroplane to South America for demonstration purposes. The debtor sold the machine and failed to account for the proceedings, and a judgment for £660 had been obtained against him. Mr Newman said that the debtor in August last was alleged to have landed in Czechoslovakia with two Spanish Nationals, and subsequently disappeared. Whether he is in Spain or not I don't know." said Newman, "but I believe he was in this country December 22 last." The case was left the hands of the Official Receiver as trustee."

The bankrupcy hearing was first delayed, then postponed indefinitely; Owen didn't turn up for any of the meetings.

He somehow became an instructor at the London Air Park Flying Club at Hanworth, an elite government-subsidized club for wealthy patrons. His fellow-instructors included David Llewellyn and Ken Waller.

Five years later, he was, somehow, a Squadron Leader in the Royal Canadian Air Force:

"In March of 1942 he was posted to Western Air Command Headquarters, but nothing is recorded in the WAC HQ diary to confirm this or indicate duties. He was then ‘Posted to ABS’ (Absent), 29 April 1942. It appears that he had gone AWOL (Absent Without Leave), as the diary of Headquarters, Western Air Command, under date of 6 July 1942, read in part, ‘Squadron Leader O.Cathcart-Jones who has been AWL for some time, returned from California to this Headquarters under escort.’ He is then shown as taken on strength of Western Air Command Headquarters, 6 July 1942. Two months later, he was ‘Retired’ from the RCAF”.

Hugh Halliday fills in some background:

"He was living in Mexico City in April 1940 when he applied to the RCAF and was duly commissioned in that force on 16 May 1940 (Pilot Officer, simultaneous promotion to Flight Lieutenant). He was assigned to the Air Member for Operations and Training, AFHQ, and performed well enough that he was promoted to Squadron Leader, 1 June 1941. The timing of this suggests (but I cannot prove it) that he was advanced in rank to give him more credibility with American authorities.

In April 1941 he was sent to California on temporary duty as Special Advisor to Warner Brothers for the film “Captains of the Clouds”. The RCAF paid him a special allowance of $ 10.00 a day for the time he was there. He seems to have considered California a bit of a “hardship posting” because of high costs and a depreciated Canadian dollar. He nevertheless wrote to people at AFHQ (Ottawa) on Warner Brothers stationery, at one point urging that he not be forgotten when operational postings were distributed. As of 20 February 1942, Hal Wallis (Director of the film) was effusive in his praise of Cathcart-Jones both in production and publicity preparation. His services with Warner Brothers apparently ended that day.

On 4 March 1942 he reported back to the RCAF on posting to Western Air Command Headquarters (Victoria, British Columbia). About a month later he was advised that he was to be posted to Station Alliford Bay as Operations Officer. A remote station in the Queen Charlotte Islands, it might nevertheless have been deemed to be in a zone of potential intense operations, given the panic that had engulfed the West Coast following the opening of the Pacific War. Cathcart-Jones would have nothing to do with it. He pleaded personal difficulties – privately he stated that he regarded Alliford Bay as a backwater – and he argued for assignment to Seattle as a Liaison Officer. On 27 April 1942, Group Captain A.D. Hull (WAC Headquarters), having interviewed Cathcart-Jones, wrote, “Squadron Leader Cathcart-Jones has undoubtedly ability. However, he appears to put his personal affairs before the Service. Should be closely supervised on new posting and given an opportunity to prove his initiative and worth.”

The same day (27 April 1942) he was issued a travel warrant to travel from Victoria to Vancouver and thence to Alliford Bay. By then he had cleared out his Victoria apartment and disposed of his books. He took the boat to Vancouver. On 28 April 1942 he crossed the border into the United States, in uniform, stating that he was on RCAF duty to the Fourth Interception Command, and that he was waiting for orders from Ottawa. He then hastened on to Hollywood.

On 29 April 1942 he wrote to Western Air Command Headquarters, submitting a resignation from the RCAF. Since he was already a deserter, the “resignation” was not accepted. In June 1942 he was arrested by American authorities, charged with having made false and misleading statements on entering the United States. He sent a message to WAC, asking that confirmation be sent that he was in California on RCAF Liaison Duty. This, of course, could not be provided (one is struck by the man’s sheer cheek). He was returned under arrest to Canada, reporting back to WAC Headquarters, and his case reviewed in detail on the 9th. Among the issues disputed were his debts ($ 884.09) and whether he should be “retired” or be allowed to resign his commission (his preference). He was retired. It was deemed that a General Court Martial for an AWOL case was “over the top” – he just was not worth it. He had not been paid since the day he went AWOL."

During his time with the RCAF he designed a board game, for which he did all the artwork; he was then involved in The Movies (Technical Director, and a 30-second appearance as 'Chief Flying Instructor' in 'Captain of the Clouds', of which Flight said " it is a first-class production in almost every respect" ).

See the excellent article on Vintage Wings of Canada's website.

He then got mixed up in some tawdry goings-on with Errol Flynn and a Miss Peggy Satterlee..

"This painting was done by Squadron Leader Owen Cathcart- Jones when he was an advisor on the movie 'Captains of the Clouds'. He also played a part in the movie. The painting shows the Hudsons Bay Co. trading post where the movie was filmed. When my father-in-law was ten years old, Cathcart-Jones gave him this lovely painting."

with thanks to http://relicsandtales.blogspot.com

He eventually bought a ranch to raise polo ponies, and became President of the Polo Club in Santa Barbara.

His daughter Imogen married John Otis Thayer (from Boston, Massachusetts) in September 1947. She was described as 'the daughter of Mrs A Cathcart-Jones of Wavedon, Bletchley, Buckinghamshire'.

Audrey died in 1962; her son Anthony in 2005.

In 1981, he wrote to 'Flight' "I had a bad accident at polo when I was knocked from my horse and fell on my head, but I am now almost completely recovered and back playing polo again."

Owen died February 1986, in California, aged 85.

Postscript

Imogen's son David actually met him: "Owen lived at 305 San Ysidro Rd., in Montecito. His ranch was about 4 acres at the end of a long driveway that passed through avocado orchards owned by the people who lived down on the road. It's been sub-divided and developed.

Some years ago, I walked up the driveway to discover that his house had been replaced by a large, pink, stucco hacienda and there's a second house, next-door, where his riding ring was. The avocado orchards down by San Ysidro Rd., are gone, too.Owen's sixth wife, and widow sold the place and moved to La Jolla a couple of years after he died. She died three or four years ago.

Imogen was reconnected with her father in the early 50s - he came to visit in 1952 and they wrote and phoned, after that.In the summer of 1965, my parents and their five kids drove out to Montecito, in a camper, and spent about a week at Owen's, just before he married his sixth ? wife, Pat, in August 1965.The following summer, 1966, I went out to visit him for two weeks, and was stranded in Montecito, for the whole summer, because of an airline mechanics strike which grounded the major airlines for 50+ days!It was great fun. My grandfather had to put me on the Continental Trailways bus, in September, to get me back to New York, in time for the first day of school.Owen had a second son, Colin, with his wife, Elizabeth Toomey, who he wooed away from her husband, in Buenos Aires, in 1936. She was married to a Mr. Waterman, who was, according to my grandfather's widow, Pat, the heir to the Waterman ink company. They married and had a son, in England, and came to NY soon after the boy was born. Evidently, in NY, he got involved with Marsinah Niesen, who was there and married to a Mr. Stebbins, and my grandfather walked out on Bette, leaving poor Bette to raise Colin in Queens, NY, with the help of her parents! She got no support from Owen.We have a January 1939 letter, from Colin's mother to my grandmother, Audrey, with her reaction to the news that Owen and my grandmother had not actually been divorced, though we do have a "Deed of Separation" which, I guess, is the precursor to divorce, in England.Bette Toomey Cathcart Jones had written to my grandmother for an affidavit of divorce so that she could proceed with her divorce from Owen. We have my grandmother's draft of the letter that she sent to Bette that prompted this response and my grandmotherher mentions Marsinah as one of the principals in her separation from Owen.Colin CJ died last January [2013]. We had Owen's passport with his and Bette Toomey's photos and Colin's name written in. I looked him up on the Internet and telephoned. We planned to meet but never got the chance. I spoke to him, just a year ago, on his birthday. November 13th." -

Cochran, Jacqueline

Jackie Cochran

b. 11 May 1906 (as Bessie Lee Pittman) near Mobile, Alabama

b. 11 May 1906 (as Bessie Lee Pittman) near Mobile, Alabama"Jacqueline Cochran's earliest memories are of life with a foster family on what she called "Sawdust Road," but what was, in fact, a lumber mill town in northern Florida. In her autobiography she remembered having no shoes until she was eight years old, sleeping on a pallet on the floor and wearing dresses made of cast-off flour sacks. As a child she was hired by a beauty shop owner, and by the time she was 13, she was cutting hair professionally. In the 1920s she became one of the first women to master the newly invented permanent wave. But one of the customers, noting Cochran's spark, encouraged her to do something more serious with her life. With very little formal education, Cochran enrolled in nursing school.

Even though Cochran completed three years of training to be a nurse, she never quite adjusted to the profession. In her autobiography, she remembers not ever getting "comfortable with the sight of blood." She constantly had to resist the urge to hand in her notice, reminding herself that a nurse was more valuable than a beautician. But she was never convinced, and an experience delivering a baby to an impoverished mother in Florida helped drive her back to the beauty trade. She remembered three children were sleeping on pallets next to the woman giving birth. "There I was with neither the strength nor the money to do the smallest fraction of what needed to be done to make those lives better... . In a beauty shop the customers always came in looking for a lift. And unless I really screwed up," she concluded, "they left with that lift."

Her next job as a beautician at Antoine's in New York's Saks Fifth Avenue brought Cochran into her future husband's world. At a dinner in 1932, the dashing millionaire financier Floyd Bostwick Odlum advised Cochran that if she were ever to realize her dream of setting up her own cosmetics firm, she'd need wings to cover enough territory to beat her competition. Cochran took the advice to heart, and that summer she learned to fly. "At that moment, when I paid for my first lesson," Cochran remembered later, "a beauty operator ceased to exist and an aviator was born."

Macrobertson Air Race in 1934

Excerpt from: "JACKIE COCHRAN, An Autobiography" by Jacqueline Cochran & Maryann Bucknum Brinley

"Gee Bee stands for Granville Brothers, a Springfield, Massachusetts, airplane company which made fast, unstable, dangerous planes in the thirties. The nearly cute nickname is a sham. They were killers. There were few pilots who flew Gee Bees and then lived to talk about it. Jimmy Doolittle was one. I was another.

I tell you all this as a prelude to my story about the London-to-Australia race. I flew a Gee Bee, the QED Gee Bee, but a Gee Bee nonetheless. The QED was Latin for "Quod Erat Demonstrandum" and came from the designers who translated that as "Quite Easily Done." It was not easily done, however. The crazy QED violated basic rules of aerodynamics.

Clyde Pangborn had entered his name in the race, hoping to find himself in a Gee Bee but, because of problems at the factory as well as an offer from Roscoe Turner, who had never flown over oceans before and knew that Clyde had, the QED was still sitting in the hangar, almost ready to go. Clyde had joined Roscoe's team but was still the registered owner of an entry.

He had the official right to name an alternate crew, and I knew it. Sitting in New York, after my conversation with Royal, searching for a way to stay in the race, I remembered Clyde's QED and made all the right calls.

Granville Brothers knew me because I myself had approached them earlier in the game but had changed my mind when I compared it with the chance to be in a Northrop. Jack's planes were so streamlined and beautifully fast for their day.

But any plane was better than no plane. I bought the Gee Bee with a little help from my friend Mabel Willebrandt. Granville Brothers were pleased because they were anxious to make a name for themselves in such a prestigious international contest. They even offered to send mechanics along to complete the plane en route to London on the ship.

In the meantime, I had Wesley Smith and Royal Leonard take some of the sophisticated equipment out of the Northrop Gamma so we could install it in our Gee Bee.

We had four hours to make the official arrangements with the London officials. I needed what was called an airworthiness certificate, numerous permissions to fly over all those countries, not in a Gamma but a Gee Bee, and Mabel turned on the steam. Mable even convinced a Department of Commerce official to go along on the boat to do the necessary testing.

Landing lights, flares, radio equipment - we planned to install as much as we could as we crossed the Atlantic, in spite of storms and seasickness. Not much would get done as it turned out.

All this was done by telephone. I never set eyes on that Gee Bee until I arrived at the airport near Southampton, England, and tried to fly it to the field where the race would commence, twenty-four hours later. It was a disaster and still incomplete. The other disastrous aspect was the tremendous publicity surrounding the contestants. I had never experienced anything like it. I never sought publicity like that in my life because mostly it's a waste of your time. And I didn't like the scene there in London one bit.

The press kept rumoring about the mysterious American woman entry, but there was nothing mysterious about my whereabouts or doings. I had a tricky, incomplete plane to contend with. In the meantime, Clyde Pangborn was giving me trouble and demanding that I pay him for the transfer of his entry. After all the anguish that Gee Bee had caused me - at that point I had no idea my troubles were just beginning - he had some nerve asking for money.

I was furious. And I told him so. If I had been a man, we would have gone out behind the hangar to fight it out....

The starting point the next morning was a nearly-completed Royal Air Force base at Mildenhall, sixty miles north of London. The lord mayor of London was there promptly at 6:30 am to drop the official white flags. Planes took off at 45-second intervals, and the famous team of Mollisons - Amy was a wonderful pilot and flew with her husband - were first. Wesley and I were fourth in line and had been warming up the engine, but as soon as we were airborne, the plane sort of staggered, dipped slightly, and I knew we were in for a real ride.

Neither of us knew that Gee Bee well enough. We recovered speed, however, and we were serious about sticking with it.

The haze was horrible and I was happy Wesley had been such a nag about my instrument training and Morse code lessons. This race, however, was actually the first and last time I relied on Morse code.

After all the hullabaloo in America about this contest, only three American-crewed entries remained: Roscoe Turner, the United States speed king at the time; Jack Wright, a stunt pilot from Utica, New York; and me. When you compared the elaborate preparations I had made for the flight - sending specialists ahead on the route with automatic refueling devices, flares, spare parts, personal items, extra instruments - as well as the whole debacle with my Northrop Gamma - to Jack Wright's simplistic attitude, I really wondered.

All Jack wanted to do en route was to "fly this plane while it's still mine". It was a tiny Lambert Monocoupe with a single 90 horsepower that hummed along. Who had more sense: him or me?

I had even sent clothes along to Melbourne so I'd have something to wear to the festivities.

But I wasn't alone with my big thinking. Roscoe Turner had gone into hock to buy a Boeing transport plane he called the "Nip and Tuck". Then because of rough weather he hadn't been able to get it off the ship at Plymouth. They had to take it over to France, to Le Havre, where the French tried to make him pay import duty of $20,000. He got around that but had to unload the plane, assemble it, and fly it back to England in time.

That was funny about all of our best-laid plans was that the Europeans had been sullen and some of them openly angry about what they believed to be a Yankee conspiracy to walk away with all the prize money.

Little did they realize. My Gee Bee was the fastest plane in the race, I believe, but right from the start I realized that it wouldn't be speed that would win.

Jackie and her co-pilot Wesley Smith were forced down by engine trouble in Rumania.

In 1953 she became the first woman to break the sound barrier in a F-86 Sabre jet fighter, earning the title 'America's Fastest Lady'.

d. 9th August 1980 in Indio, California, aged 74

-

Davies, Cyril G

F/O Cyril G Davies

Partnered Lt-Cmdr E M Hillin the MacRobertson Race

AHSA_1985_AH_Vol_24_No_1-2 says:

"The pair who had flown together in the Fleet Air Arm became known as “Burglar Bill and the Missionary”. Davies earned the title of the “missionary” no doubt because since leaving the R.A.F. some time previously he had been running a shelter for destitutes in the West End of London.

-

Geijsendorpher, Gerrit Johannis

Gerrit Johannis Geijsendorpher

Born 1st April, 1892 in Sliedrecht

Born 1st April, 1892 in SliedrechtLike Koene Dirk Parmentier, Gerrit also died in an accident in KLM service. On 26 January 1947 his Douglas DC-3 crashed shortly after takeoff from Kastrup Copenhagen Airport in Denmark, killing all 22 on board.

Among the victims were the Swedish prince Gustav Adolph and the American singer Grace Moore.

-

Gilman, Harold Darwin

Harold Darwin Gilman

b. 29 April 1906 in Neutral Bay, Sydney

b. 29 April 1906 in Neutral Bay, SydneyDied on 23rd October 1934 in Italy (crashed during the MacRobertson Race), aged 28

"Flt. Lt. Gilman took his "A" in 1926 with the Auckland Aero Club. Shortly afterwards he joined the N.Z. Staff Corps and was sent to Aldershot in 1928 on attachment to the Suffolk Regiment. In 1929 he was transferred to the R.A.F. "Refreshed" at No. 2 F.T.S. (Digby), he was posted to No. 101 (Bomber) Sqd. at Andover, under Wing Com. F. H. Coleman, whose adjutant he remained until 1933. Gilman took part in all squadron experiments, including the high-precision bombing of H.M.S. Centurion. Last year, on conclusion of the annual Combined Exercises, he was sent as assistant adjutant to No. 600 (City of London) Sqd. under the late Sqd. Leader S. B. Collett. Finally, after brief attachment to the C.F.S. (Wittering), he was posted to the newly formed No. 15 (Bomber) Sqd. at Abingdon, of which he commands "B" Flight. His log-books show 1,560 hr.

Gilman has been granted special leave to accompany Baines in the race to Australia."

-

Hansen, Michael

Michael Hansen

b. 14 January, 1903

b. 14 January, 1903Trained as a pilot in the Danish Army Air Force in 1927. Just before the MacRobertson Race, had competed in an aerobatic championship in Paris.

He flew with mechanic Daniel Jensen, who crouched under the main petrol tank which was fitted instead of the passenger seat. The Desoutter was already over 3 years old by 1934.

----------------

BRITISH AEROPLANES FOR DENMARK

Eight De Havilland Machines for Danish Air Force WITHIN the next few days a fleet of eight de Havilland aeroplanes will leave Harfield aerodrome to fly to Copenhagen in charge of officers of the Danish Air Force. The flight will be under the command of Capt. C. C. Larsen, who will pilot the "odd" machine of the flight, a de Havilland "Dragon." The other seven machines are "Tiger Moths."

The seven " Tiger Moths " will be used for the instruction of Danish pilots in the art of military air manoeuvres, and the equipment of the machines includes all the instruments necessary for "blind flying." Instrument flying is a relatively recent development of military flying training, and Great Britain has, perhaps, done more than any other nation to perfect the equipment. Following the adoption of instrument flying by the British Royal Air Force, nearly all other nations are adding it to their curricula.

The "Dragon" bought by the Danish Air Force is equipped for military purposes, and will also be used for light transport and for aerial survey. All the machines of the batch are fitted with de Havilland "Gipsy Major" engines.

WAITING TO GO : Seven "Tiger Moths" and one "Dragon" at Hatfield, ready to start for Copenhagen. The Danish crews include Capt. C. C. Larsen, Lts. Clausen, Meincke and Rydman, Sgts. Eriksen, Petersen and Hansen, and Machine Officer Petersen. (FLIGHT Photo.)

The Hop to Darwin (by Lord Sempill)

1 WAS just preparing to make a start for Darwin when a D.H. " Moth," which had been very kindly sent over by the Vacuum Oil Co., landed to see if I was all right. Apparently the signal sent from Koepang, although it had reached them, had not Been very clear as to my intention to stop the night at Bathurst Island. They brought my mail which, of course, was mostly from Australia, and contained numerous hospitable invitations. Taking off on the short sea crossing, I arrived at Darwin and received a very kind welcome. The aerodrome has a level grass surface, but is, I understood, liable to become boggy after rain. It is 680 yards from north to south and 1,000 yards from east to west. There is a well-equipped meteorological office and a new shed was just being built. The Danish pilot, Lieut. Hansen, who had put up such a good performance in the MacRobertson race in an old Desoutter, was here on his return journey. He was hurrying home as he had only been given leave from his military duties until December 10. He had done some hard flying on the outward trip, putting in, on some sections of the route, sixteen hours a day.

MARCH 7, 1935 - 'Flight'

A British Entry for International Aerobatic Contest ?

ORGANISED by the newspapers Le Petit Parisien and Air Propagande, an international aerobatic competition, named " Coupe Mondiale d'Acrobatie Ae'rienne," will be held at Vincennes, near Paris, on June 9 and 10. The prizes amount to 300,000 francs, of which 100,000 will be awarded to the winner, 75,000 to the second and 50,000 to the third. It is reported that the following entries have been received:—

Detroyat (France), Al Williams (U.S.A.), Fieseler (Germany), Colombo (Italy), Staniland (Great Britain), Orlinsky (Poland), Hansen (Denmark) and Van Damruch (Belgium).

Judging from what we have seen of Staniland's masterly handling of the " Firefly," he should have little to fear from the aerobatic " aces " of other nations.

FLIGHT, FEBRUARY 15, 1934

The Danish Air Society (Det Danske Luftfartselskab) bought the second last manufactured Desoutter Mk.II in 1931. This aircraft was given the registration OY-DOD. In 1934, this aircraft was sold to lieutenant Michael Hansen, and in the following year to the Nordisk Luftrafik company. In 1938 it was sold to Nordjysk Aero Service, but Michael Hansen bought the aircraft back the same year and used it to fly to Cape Town and in the MacRobertson Air Race

Michael Hansen, 14.1.1903-23.3.1987, Danish pilot. Michael Hansen was trained as a pilot in the Army Air Force troops in 1927. Han achieved a seventh place (out of 20 runners aircraft) with a single-engine FK Desoutter højvinget monoplane in October 1934, together with maskinofficiant Daniel Jensen in the famous air racing Mildenhall (England) - Melbourne (Australia) in competition with some of the world's most talented pilots and fastest planes. It was a trip of no less than 19.895 km.

In 1937 flew he and engineer Aage Rasmussen to Cape Town and return with the same aircraft. The following year he participated in a Danish military søfly (De Havilland DH82A Tiger Moth) as islods on Eigil Knuth Dark Northern Expedition to Northeast Greenland. These flights he described in the books "43.000 km through the air" (1935) and "On the Danish wings in South and North "(1941). He was in a number of years president of The Adventure Club and ended his military career in 1963 as a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force. He is buried in Hørsholm Cemetery.

Literature: Michael Hansen: 43.000 km through the air (1935) and the Danish wings in South and North (1941), Ove Hermansen: Since Hansen flew to Melbourne in '34 - 75 years for Danish participation in the world's largest flykapløb from England to Australia (2009).

-

Hemsworth, Godfrey Ellard

Godfrey Ellard Hemsworth

Seen here on the left, in 1940

Godfrey's signature:

Godfrey (‘Goff’) Hemsworth and ‘battling’ Ray Parer piloted a second-hand Fairey Fox biplane, G-ACXO, in the 1934 England to Australia Air Race. Although they almost immediately had engine trouble (over the English Channel, in fact) and didn’t complete the course in the time allowed to qualify for any of the prizes, they battled on... and on; eventually, they took 117 days to get to Melbourne. But they got there!After the race, Godfrey joined the RAAF and was killed in the Battle of the Coral Sea, flying a Catalina.

"'Goff' had all the guts in the world." They say.

[family insights were kindly provided by G E Hemsworth, Godfrey's nephew].

Family

Godfrey was born in Sydney, Australia on the 2nd of January, 1910. He had three brothers - John, Neville and Hugh - and two sisters, Alice and Anne.His grandfather (John) had owned and captained a number of vessels (including the Neville & Costa Rica Packet), but during the 1890’s depression most of the fortune had been lost.

His father, Captain Hemsworth – also (confusingly for us) called Godfrey Ellard – had been instrumental in the exploration of New Guinea during the latter part of the previous century; in 1885, the Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser reported that:

“Godfrey Hemsworth, age 23, of Brisbane, filled the post of nautical sub-leader, and in the event of the death, or serious illness, of the leader he would take his position, except that he would not lead the party on land. He held a master's Certificate, and had been navigating officer of some of the finest steamers, was a member of the Meteorological Society of London, and was qualified to undertake any kind of marine surveying.”

Theodore F Bevan, of the RGSA, wrote about that expedition and the subsequent gold rush in his book ‘Toil, travel and discovery in British New Guinea’.

However, by 1906 Captain Hemsworth was listed as a 'pearler' in the electoral roll for Broome, Coolgardie, living in Weld Street. (A ‘pearler’ (leaving aside its use as an Australian slang word meaning ‘excellent’ or ‘good-looking’!) is someone that ‘dives for, or trades in, pearls’). There was obviously enough money for him to purchase some pearling luggers (in the end he owned 12 including the Blanche –named after his niece - and some others named after his sisters). He left Broome in 1908 and returned to Sydney.

It was while he was in Western Australia that he met Mabel; they married in Feb 1907. She was 'about 30 years younger than her husband' (who would have been about 45 at the time!)

Godfrey's nephew G E Hemsworth told me "Interestingly, I have a journal that a great aunt wrote about her life and that of her parents and siblings. It traces their lives from 1825 to the 1930’s, but not once does she mention Mabel, so obviously the family were not happy!"

Captain Hemsworth died in 1923. His estate amounted to about £12,000, which he left ‘for the benefit of his widow and six children’. Using average earnings, this would be worth over £2 million today.

Before the Race

Godfrey took his A and B pilots’ licences with the local branch of the Australian Aero Club in 1931, and then flew for Parer's New Guinea company. Not without incident, however:

“Mr- Mario Coucoulis, secretary to the Greek Consul-General in Sydney, left Mascot aerodrome on Saturday on a flight to Perth. His idea is to gain experience for a projected flight to Greece later in the year. Mr. Coucoulis and Pilot G. E. Hemsworth, who were flying from Sydney to Perth, made a forced landing near Wagga on Monday. The plane was damaged, but neither occupant was hurt. They intend to proceed when repairs are effected.”

The Queenslander, Thursday 23 July 1931

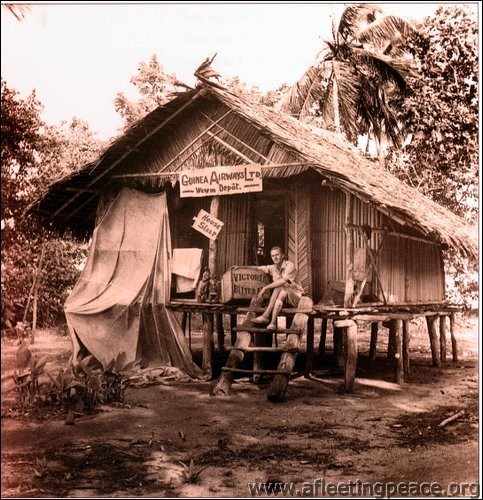

During the 1930s,when Papua New Guinea was governed by Australia, a quite extraordinary air-based operation was mounted in Bulolo to support the gold mining industry– so much so that New Guinea ‘led the world in commercial aviation’ at the time.

Bulolo during the gold rush days

In 1933 Godfrey and his brother John were living at Wychwood, Condamin Street, Balgowlah, New South Wales (although both were listed as having ‘No Occupation’). Their mother, Mabel, lived nearby in White Street.

Parer and Hemsworth arrived in England from New Guinea on August 6, 1934, breaking the journey at Singapore. The Fairey Fox in which they competed in the Air Race was bought from the Hon. Mrs. Victor Bruce, and was modified at Hanworth by W. S. Shackleton, who ‘cleaned it up very prettily’.

After the Race

In September 1936, there is a curious entry in the Sydney Morning Herald:“AMBITION TO FLY: Youth Granted Fees from Estate

Application was made in Equity yesterday by Neville Hemsworth, a son of the late Captain Godfrey Hemsworth, retired master mariner, formerly of Campbelltown, for an order for the payment of fees from his father's estate for the purpose of applicant's training as an aviator.

The application was made through the applicant's mother, the testator's widow, a resident of Manly. She said that her son Neville had just left school. He was aged 19, and wished to qualify as an aviator to obtain a pilot's "A" licence, and "B" commercial licence, and wireless and navigation licences. One of his brothers, Godfrey, was a pilot for New Guinea Airways at a salary of £900 a year.

Mr. Justice Nicholas made an order authorising the trustee to pay out of corpus £475 to meet the fees necessary for the purpose indicated, and in addition, £25 for books, instruments, etc.”

"... It’s an interesting story. My grandfather’s will gave the boys their money at 25, the girls were to receive a monthly payment. As Neville wanted to learn to fly he had to have access to the funds earlier and Mabel successfully argued that sufficient funds should be released to enable Neville to obtain his pilots license. When Godfrey died in 1923, the oldest child (John) was 15 and the youngest Hugh only a few months old. Mabel had many fine qualities and was certainly a loving mother however she was not good with money and of course six years later in 1929 the start of another depression and a second fortune lost. This indicates how important it was for Neville to obtain a good job and learning to fly would help achieve that."

…although Godfrey's working for ‘New Guinea Airways’ may not have been as glamorous as it sounds…

RAAF