|

Geoffrey Junior, aka 'Young D.H.' born in 1910 and learnt to fly at Stag Lane at a tender age. Took over as chief test pilot at de Havillands when Bob Waight was killed.

Second Brit to fly a jet-propelled aircraft on its first flight, the Vampire in 1943. Killed when the second DH108 Swallow broke up and crashed in the Thames estuary in 1946.

Flight 18th April 1946

As a test pilot young D.H., as he is universally called,has not an exceptionally long history. He took over the chief test pilot's position in October, 1937, when R. J. Waight unfortunately lost his life on the T.K.4. Being, however, the son of his illustrious father, Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, who designed, built and test flew his own aircraft from 1911 onwards, young Geoffrey can be said to have been ''in the industry'' from the very cradle. It is not generally known that Sir Geoffrey took his R.Ae.C. ticket No. 53 in February, 1911, on the second machine of his own design and construction, and that he has made many of the first flights on new D.H. types right up to the Moth Minor in 1938.

Geoffrey's first flight is lost in the dim past, but certain it is that at the tender age of six he was flying with father at Hendon in a D.H. 6 (also known as the Clutching Hand). When 18 years of age he left school and came to de Havillands as a premium apprentice for 4 years and learnt to fly on Moths at the firm's reserve training school. After spending two years in the drawing office—much of the time being spent looking out of the windows envying the pilots—he joined the Air Operating Company, who were doing a lot of air survey work in South Africa. This, however, gave him but very little flying, and at the end of six months, he came back to England to become a flying instructor to the D.H. Technical School. The aircraft were wooden Moths built by the students. In 1929 he took his B licence; a very simple business in those days. Some 20 or 30 hours' solo flying, a little cross-country work, a simple "Met" exam, and about one hour's night flying at Croydon was sufficient to qualify.

In 1934 Capt. Hubert Broad was chief test pilot of de Havillands, and Bob Waight looked after the production side. There was so much work, however, that Geoffrey was given the opportunity to lend a hand testing Tiger Moths, Dragons, Rapides, Express Air Liners, and Hornet Moths.

Broad left the company in 1935 and Waight took over, starting, with the Dragonfly and later the Albatross. It was during the period when the prototype Albatross was going through its development flying that Waight lost his life, and de Havilland took over as chief test pilot. Nobody could have taken on a more interesting or more complex job because the Albatross was completely experimental from tip to tail. Engines were new, construction was new, and the layout was extremely advanced.

He had a curious experience on the Albatross. While its strength was ample for all flying loads, some unfortunate drilling had weakened the fuselage under ground loads, and shortly after landing from a test flight the machine broke in halves on the ground.

When war broke out lie was busy testing Oxfords and Flamingoes, but when things became desperate at the time of the Battle of Britain, de Havillands did a big job doing emergency repairs to shot-up Hurricanes.

Dick Reynell of Hawkers came over and gave Geoffrey the "know how" on Hurricanes. A little later Dick went out on operations with his old squadron (No. 43) and was, unfortunately, shot down.' He was an excellent test pilot and a gallant gentleman.

Improvised Runway

Geoffrey flew the first Mosquito at Hatfield on November 21st, 1940, but he is more proud of the first flight of the prototype Mosquito fighter. This was built at a dispersal factory with no airfield. To save some six week's wasted time in transport and re-erection at Hatfield, Geoffrey used local fields by having bridges built over ditches to give him a 450yd run for take-off, and then flew the fighter to Hatfield.

He is, of course, one of the only two men in Britain to have made first flights on jet-propelled aircraft. The Vampire was flown for the first time on September 21st, 1943, but Geoffrey had already flown the Gloster E.28 at Farnborough. The first airing of the Vampire proved it to be a tribute to the D.H. design and aerodynamics staff, as it behaved almost exactly as they had forecast. There was, however, somewhat of an aileron overbalance which limited the speed to 250 m.p.h. and a rather severe tip stall.

Geoffrey de Havilland had made a number of investigation flights on Mosquitoes for compressibility effects, but on the Vampire he has done extensive work. The Vampire, under the effects of compressibility, executes a series of sudden high-speed stalls: the path of the machine is similar to an artist's conception of a streak of lightning, and unless the pilot is strapped-in tightly he is likely to be knocked out by hitting the cockpit roof.

Geoffrey, with another pilot, has flown the Vampire in tight formation at over 500 m.p.h., and to investigate snaking, which is causing considerable trouble on most jet aircraft, he has flown the Vampire with rudder locked.

Like most of the test pilots, he is living on borrowed time, they having at some stage of their careers had close shaves. Strangely enough, Geoffrey's nearest go was on about the mildest type he ever flew. It was the first production Moth Minor. The prototype had completed its spinning tests, and the same tests on the production model appeared to be only a matter of form. He was flying with John Cunningham (now Group Capt., D.S.O.,D.F.C., and test pilot for the D.H. engine division) at the time. The Minor was put into a spin at 5-6,oooft, but after it had failed to come out in five turns and the engine had stopped, a panic decision was made to abandon ship.

Test-flying a Hurricane, too, almost saw him off. This particular aircraft had had a gruelling time in the Battle of Britain, and the whole canopy came off at 4,000ft.hitting him in the face as it blew backwards. At first blind through the amount of blood in his eyes, he flew more by instinct than anything else until he found he could get a little relief by holding his face close to the instrument board. The blood dispersed a little and he was able to land through what appeared to be a thick yellow haze. He wears the scars across his nose to this day, and there was a terrible moment during that flight when he thought he was really blind.

On another occasion the oxygen bottle contained only compressed air, and the effects from this were at first blamed on the previous night's party.

At the other end of the scale was the test of the T.K.5, a tail-first aircraft built by the technical school. Impecunious at the time, Geoffrey had already mortgaged the bonus for the first flight. Imagine his consternation then when, after roaring the whole length of Hatfield airfield, the machine showed no sign of lifting. The forward elevator was ineffective. The T.K.5 never did fly and was finally abandoned.

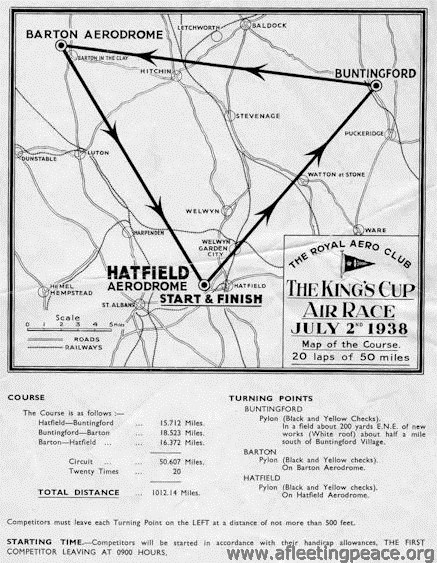

In the days of peace before the war Geoffrey de Havilland was to be seen at all the air meetings and twice finished 4th in the King's Cup Race flying the TK1 and TK2.

|

Click here to see the Newsreel!

Click here to see the Newsreel!

in 1930, aged 22

in 1930, aged 22 1936

1936 in 1936, aged 28

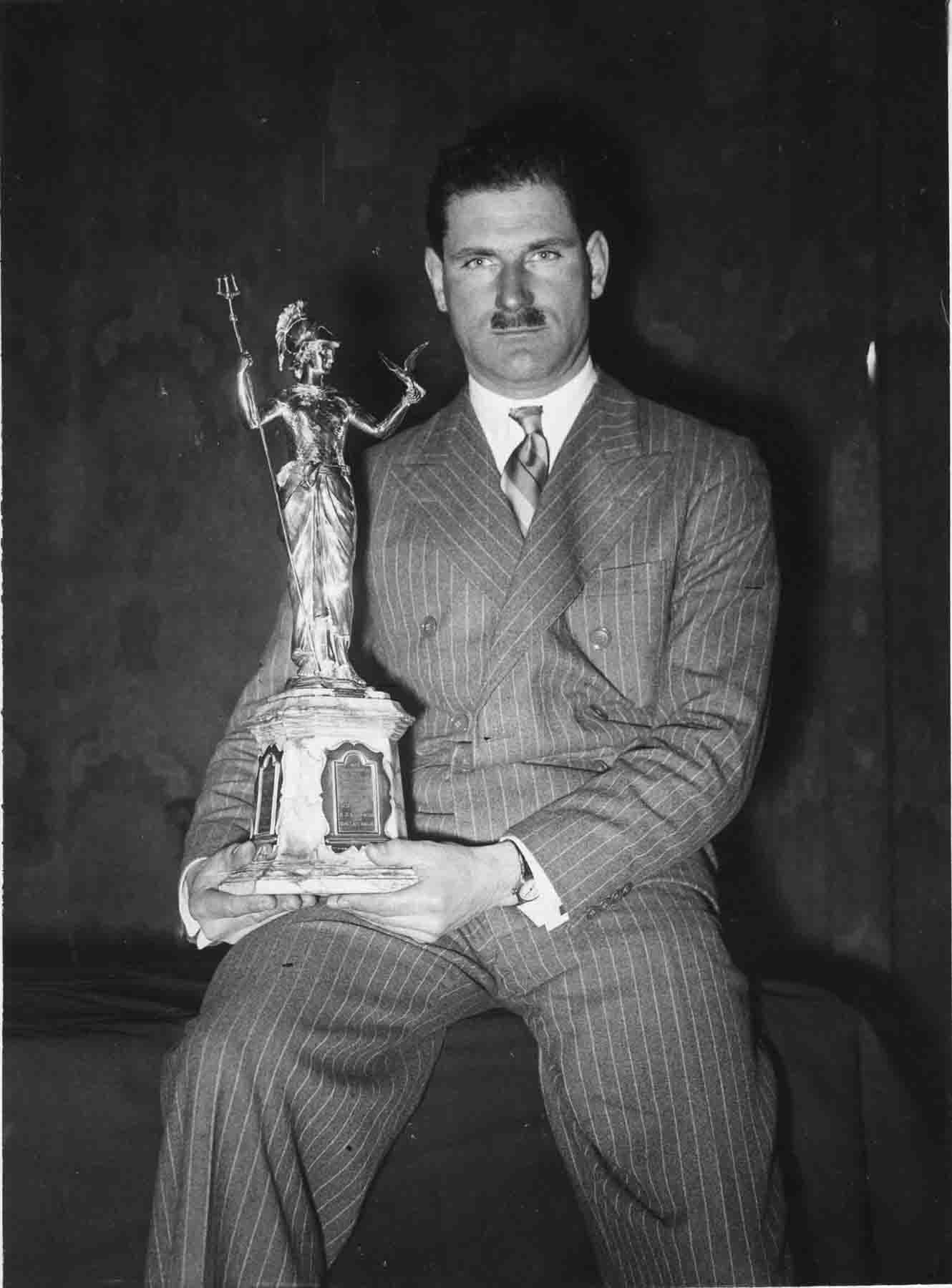

in 1936, aged 28 With the Brittania Trophy

With the Brittania Trophy 1936

1936 1931, aged 26

1931, aged 26

1934, aged 21

1934, aged 21 1938

1938

1935, aged 19

1935, aged 19 1936

1936 1932, aged 20

1932, aged 20 1933, aged 24

1933, aged 24

1932, aged 21

1932, aged 21 Flight

Flight

AJJ

AJJ

1930, aged 32

1930, aged 32 King's Cup 1934; sans trilby, for once

King's Cup 1934; sans trilby, for once In 1956, with the EP.9 'Prospector'. And trilby.

In 1956, with the EP.9 'Prospector'. And trilby. 1938, aged c.25

1938, aged c.25 1930, aged 29

1930, aged 29 1930, aged 22

1930, aged 22

1933, aged 22

1933, aged 22 1936, aged 28

1936, aged 28