King's Cup - 1934

-

-King's Cup - 1934

Click here to see the Newsreel!

Click here to see the Newsreel!

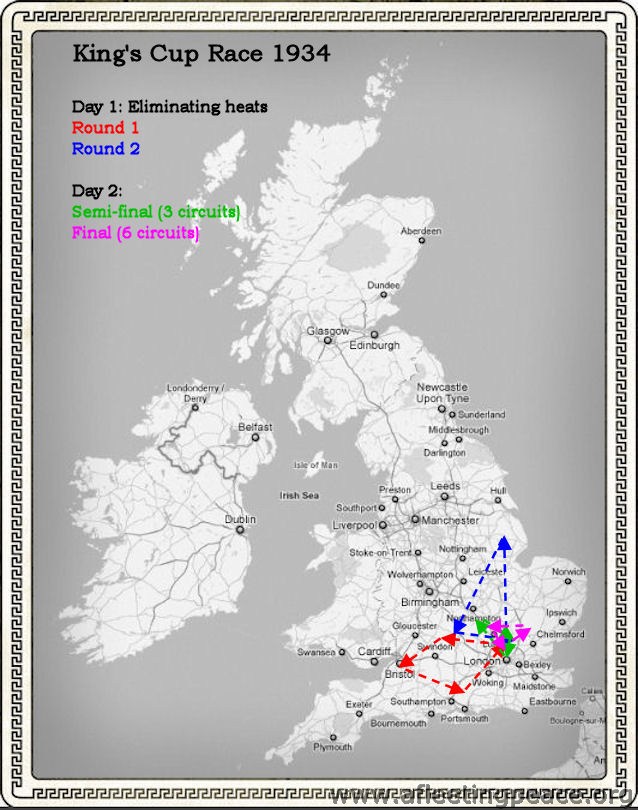

Edgar Percival in the Mew Gull 13th and 14th July, 1934. Hatfield

Weather: Awful on the Friday, better on the Saturday.

Story of the Race:

Pilot: Aircraft Race No Fate Mr T AK Aga D.H.60G III Moth Major G-ACPH 1 forced landing at Reading - fuel problem Mr Geoffrey R de Havilland de Havilland Technical School T.K. 1 G-ACTK 2 5th Mr A H Cook Comper Swift G-ABWW 3 eliminated in Round 2 Mr Alex Henshaw D.H.85 Leopard Moth G-ACLO 4 eliminated in Round 1 Mr W H Sutcliffe Hawker Tomtit G-AASI 5 7th Wing-Cmdr J W Woodhouse Hawker Tomtit G-ABAX 6 retired at Whitchurch in Round 1 - broken aileron rod Mr G E Lowdell Hawker Tomtit G-ABOD 7 eliminated in Round 2 Flt-Lt E A Healy Comper Kite G-ACME 8 eliminated in Round 1 Mr H F Broadbent D.H.83 Fox Moth G-ACSW 9 8th Mr T W Morton D.H.85 Leopard Moth G-ACHC 10 disqualified in final - missed turning point F/O J Beaumont D.H.85 Leopard Moth G-ACOO 11 eliminated in Round 1 F/O H RA Edwards Southern Martlet G-AAYZ 12 6th ACM Jackaman GAL ST.4 Monospar G-ABVP 13 eliminated in Round 1 Flt-Lt H M Schofield GAL ST.10 Monospar G-ACTS 15 winner Mr V G Parker D.H.85 Leopard Moth G-ACPK 16 eliminated in Round 2 Flt-Lt H M David Blackburn B2 G-ACAH 17 4th Flt-Lt R PP Pope Comper Swift G-ACML 18 eliminated In semi-final Mr E W Percival Percival Mew Gull G-ACND 19 eliminated in Round 1 Sir Charles Rose Miles M.2E Speed Six G-ACTE 20 landed at Northolt in Round 1 - ignition trouble Flt-Lt J B Wilson Desoutter I G-AAPZ 21 eliminated in Round 2 Mr E H Newman Comper Mouse G-ACIX 22 eliminated in Round 1 Mr Peter J de Havilland D.H.82a Tiger Moth G-ACJA 23 eliminated in Round 2 Lieut Owen Cathcart Jones D.H.80a Puss Moth G-ABLS 24 9th Mr J D Kirwan Percival D.2 Gull Four G-ACGR 26 eliminated in Round 2 Mr A LT Naish Hendy 281 Hobo G-AAIG 27 eliminated in Round 1 Mr S W Sparkes D.H.85 Leopard Moth G-ACKN 28 eliminated In semi-final Flt-Lt H H Leech Percival D.3 Gull Six G-ACUP 29 eliminated in Round 1 Capt Geoffrey de Havilland D.H.87 Hornet Moth G-ACTA 30 eliminated in Round 1 Mr C E Gardner GAL ST.6 Monospar G-ACIC 31 eliminated In semi-final Mr D Shields D.H.60G Moth G-AAZE 32 Landed at Reading in Round 1 Capt W L Hope Percival D.2 Gull Six G-ACPA 33 eliminated in Round 1 Mr Laurence Lipton D.H.60G III Moth Major 'Jason 4' * G-ABVW 34 3rd Mr S P Symington Comper Swift G-ABZZ 35 eliminated In semi-final Flt-Lt N Comper Comper Streak G-ACNC 36 eliminated in Round 2 A-V-M A E Borton Airspeed AS.5 Courier G-ACNZ 37 eliminated in Round 1 Capt R G Cazalet GAL ST.4 Monospar 2 G-ACHU 38 eliminated in Round 1 Mr A CS Irwin B.A. Eagle I G-ACPU 39 eliminated in Round 1 Mr C S Napier Hendy 302A G-AAVT 40 eliminated in Round 2 Mrs G RM Patterson Miles M.2 Hawk G-ACIZ 41 retired at Peterborough in Round 2 - weather Mr Tommy Rose Miles M.2F Hawk Major G-ACTD 42 2nd Capt H S Broad D.H.89a Rapide G-ACPM 43 eliminated in Round 2 * which formerly belonged to Amy Johnson

Starters: 41 (out of 43 entries)

Did not start:

Mr E G Hordern BA Swallow L25C Mk.2 G-ACTP 14 Mr G W Ferguson Parnall Heck 2C G-ACTC 25 Handicapping Madness:

Edgar Percival posted the highest average speed of any competitor, at 191 mph, and was eliminated in the very first Heat.

Gabrielle Patterson posted the second-slowest average speed of any competitor, and won her Heat.

You can see her point. (see her article Air Race Handicapping)

-

-The Aviators

The Aviators

-

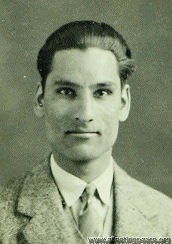

Aga, Tariq Ali Khan

Tariq Ali Khan Aga  photo: 1933, aged 24

photo: 1933, aged 24 -

Broad, Hubert Stanford

Capt Hubert Stanford Broad MBE AFC

photo: 1930, aged 33

photo: 1930, aged 33b. 18 (or 20) May 1897

shot through the neck in WWI by one of Richtofen's Red Circus pilots; [c.f. Angus Irwin]; second in Schneider 1925, to Jimmy Doolittle.

In 1928, he spent possibly the most boring 24 hours of his life by beating 'all existing figures' for long endurance flights in light aeroplanes (unfortunately there was no official 'record' to beat as such, the FAI not recognising such things). His log makes, um, rivetting reading:

--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--

5:30pm: Hendon

7:40pm: Gloucester

8:30pm: Coffee and sandwiches

11pm: Over Central London, 3,000ft; watched theatre crowds leaving

Midnight to dawn: Remained over Edgeware

2:30am: second meal

4:10am: First signs of dawn

5:10am: Biggin Hill. Saw night bomber in air

...

Noon: Stamford. Very sleepy

4:30pm: Ipswich

--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--0--

Having trimmed the controls, Hubert settled down and read 3 complete novels 'to relieve the boredom'.

When he finally landed, he he said that he was very stiff with cramp, and promptly went home to sleep. His Moth still had 12 gallons of fuel, so it could have kept going for another 4 1/2 hours...

He was named as co-respondent in Beryl Markham's divorce in 1939.

de Havillands test pilot until 1935 (Bob Waight succeeded him) - broke the world's speed and height records for light aircraft in the original monoplane Tiger Moth, then joined RAE Farnborough; Hawker test pilot post-WWII; died 1975

FLIGHT MARCH 28TH, 1946

No. 2. CAPT. H. S. BROAD, Senior Production Test Pilot, Hawker Aircraft Co.

FOR sheer wealth of flying experience it is doubtful whether there is another pilot in the world to equal Hubert Broad. He has flown everything from diminutive single-seaters to multi-engined--bombers, and including a number of out-and-out racing aircraft. His logbooks, of which he has filled some nine or ten, total over7,500 hours' flying time and 182 separate types. These are honest types—not modifications or different mark numbers of the same aircraft. Many of these he has also flown as seaplanes. Broad, at the age of nineteen, learnt to fly at the Hall School of Flying at Hendon in 1915. The aircraft on which he made his first flight (there was no dual, a pupil did straights across the airfield until he felt it was safe to do a circuit)was the single-seater Caudron with35 h.p. Y-type Anzani engine. Believe it or not, with this tiny horsepower the Caudron occasionally was made to stagger into the air with two people on board, but the passenger had to sit on the wing by the side of the nacelle.

Early Days

The end of 1915 found Broad in the R.N.A.S. at Eastchurch, and he was on the very first course at Cranwell, which was then a R.N.A.S. establishment rejoicing in the name of H.M.S. Daedalus. His first tour of duty at the front was with No. 3 Squadron at Dunkirk. He was among a number of pilots lent by the R.N.A.S. to the R.F.C. No. 3 Squadron flew Sopwith Pups, and it was while he was on one of these, escorting a bombing raid by 90 h.p. R.A.F.-engined B.E.s, that he was shot through the neck by one of Richtofen's later Goering's—Red Circus pilots.

On recovery he spent a while as an instructor at Chingford and then went for his second tour of operations with No. 46 Squadron, who flew Sopwith Camels. The end of the 1914-18 war found Broad instructing at the Fighter Pilots' Flying School at Fairlop.

Peace found him, as it found so many other young fellows ,with the ability to fly aircraft superbly and no other means of making a living. But a good living could be made by joy-riding in the early 1920's. First he joined the Avro Company, who were running joy-riding in a fairly big way, and in 1920 went to the Adiron Lakes in America with two Avro 504 seaplanes. These two aircraft saw their last days in Long Island, where they were completely wrecked by an autumn gale.

By the next year he was back in England competing in the Aerial Derby air race round London on a Sopwith Camel. He finished 6th.In October, 1921, Broad joined de Havillands. Those who know this great concern now will smile to learn that when it started in those days it consisted entirely of two fabric hangars and a hut at Stag Lane. If memory serves, the capital of the company at that time was £100.

The D.H. series numbers, which started in the Aircraft Manufacturing Co. Ltd., were carried on in this new firm, and Broad flew every one of the D.H. designs from the D.H.27 to the D.H.90. In the same period he did a lot of test flyingfor other aircraft constructors.

He did the W.10, Handcross, Hendon, and some others for Handley Pages, the Parnall Pipit and the Saunders A. 10 fighter. On the Gloster Grebe he ran into wing flutter for the first time (this trouble, in those days, was on a par with the compressibility troubles we have now).

Seaplane testing

Another big job he did was most of the development work on the Gloster II and III racing seaplanes. Over a period I used to go with him to Felixstowe regularly. As a Press man I was forbidden the precincts of the R.A.F. seaplane station, but there was a perfectly good Great Eastern Railway pier alongside the station. I used to climb over the fence and watch the proceedings from the pier head. Broad nearly lost his life there one day in October,1924. As he was landing the Gloster II a forward strut to the floats collapsed, and the aircraft turned completely over. Mrs. Broad was watching from the shore, and it seemed a very long time before Hubert appeared on the surface.

In 1925 Hubert Broad flew the Gloster III racing seaplane in the Schneider Trophy contest which was held that year over Chesapeake Bay in America. This was the race in which Henri Biard, flying the SupermarineS.4—the true forerunner of the Spitfire—crashed in the water with wing flutter. Broad finished this race second to Jimmy (now General) Doolittle. That must have been a vintage generation, because many names from that period have found their way into the high-spots of this last war.

With the advent of the D.H. Moth in all its variants, Broad was to be seen performing aerobatics at most flying club meetings and entering many of the races. These included the King's Cup Race, which he won in 1926. He was flying a delightful Cirrus I Moth, which was a study in ivory and red. His average speed over the whole732 miles was 90.4 m.p.h. His piece de resistance in aerobatics was a perfectly formed big loop, the base of which was only some 150ft from the ground. It was a joy to behold, but very dangerous to perform. Broad had sufficient sense to realise this and sufficient courage to stop doing it.

"Hooked"

It was during an aerobatic show that Hubert had his closest shave in a life packed with incident. And it was so simple. Flying a D.H. Tiger Moth with no one in the front seat, he did a slow roll—a stunt at which he was a master. The safety belt in the empty cockpit was loosely done up. While the Moth was inverted the belt hung down and, as the aircraft turned the right way up again, the belt came back over the joy-stick. The result was that Broad had only about 1 1/2 inches of stick movement; but, nothing daunted, he made a sort of tail-up, seaplane landing. In this connection it is to be remembered that there were no lovely 2,000-yard runways on which to this sort of thing. In those days there was not a single runway available in Britain; not even for the take-off of over-loaded aircraft for long-distance records!

Another unhappy moment occurred when he found the tail trim (the incidence of the whole tailplane was adjustable)of a D.H.34 had been connected in reverse. By a good deal of jockeying he managed to get into Northolt. On yet another occasion a careless mechanic left a screwdriver jammed in the chain and sprocket of the rudder actuating gear. This necessitated a down-wind, crosswind, finishing up into-wind landing at Hendon airfield, because that was a bit bigger than Stag Lane.

One of the prettiest little aircraft he ever flew was the original D.H. Tiger Moth monoplane. This was tailored exactly to fit Broad. Physically he is not of big stature and few other pilots could get into the machine. In the front of the cockpit was a bulkhead which had two holes just large, enough for the feet to be threaded through, and these holes had to be padded with sorbo rubber so that Broad's shins did not get barked while landing and taxying. Springing was almost non-existent. Span was22ft 6in and length only 18ft 7m.

In August, 1927, on this machine he broke the world's record for light aircraft for both speed and height. For the former the figure was 186.47 m.p.h., he having taken19 min 59 sec to cover the 10 km, and for altitude he reached 20,000ft in just 17 min. A year later he took two more world's records on the D.H. Hound.

In 1935, after 20 wonderful years of service, he left de Havillands and later did some flying for the Air Registration Board. From here he went to the Royal Aircraft Establishment and finally joined Hawkers to be in charge of all their production testing at Langley. He will be 50 in a matter of a few weeks, yet every day sees him at oxygen height testing Tempest IIs. As he says, he has gone from 35 h.p. in the Anzani to over 3,000 h.p. in the Centaurus and Sabre VI, and from 2 ½ lb/sq ft in the Caudron to 40 lb/sq ft in the Tempest II.

-

Broadbent, Harry F J

Mr Harry F J Broadbent

photo: 1937, aged 27

photo: 1937, aged 27Australian record-breaker (solo round-Australia record in 1931), born 1910.

Listed polo, tennis, golf and cricket among his other pastimes.

-

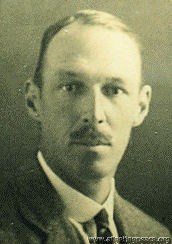

Cathcart Jones, Owen

Lt Owen Cathcart Jones

1934

1934 Born 5th June, 1900, London (definitely not Canadian, despite some nasty rumours).

McRobertson Centenary Gold Medal 1934

Royal Aero Club Silver Medal 1934

Holder of 8 Long Distance World Records. 1934

It's difficult to know what to make of Owen Cathcart-Jones, really; he was handsome, adventurous, undoubtedly talented, and clearly an excellent aviator - but, I'm afraid, rather prone to go 'AWOL' - both in his personal and service life!Born in London on 5 June 1900, he joined the Royal Marines in 1919, then, after the usual period of general service he volunteered for flying and joined R.A.F Netheravon on 12 January 1925, in the first batch of Marines officers to be transferred.

He was awarded his 'wings' in August 1925 and was posted to RAF Leuchars, serving with 403 Flight on HMS Hermes, and 404 Flight on HMS Courageous, taking a hand in the troubles in China in 1926-27 and again in Palestine in the following year.

In 1927, he wrote to The Times:

Sir,

On July 17 I had occasion to be flying down the east coast of Greece, and when in the vicinity of Mount Kissavos, near Larisa, I was astonished to see a large golden eagle fly past my aeroplane on a parallel course at a distance of about 80 feet away. The bird did not appear to be at all concerned at the noise of the engine, and in fact turned its head round to look at the aJrcraft on passing. The speed on my indicator showed 70 knots, and the height by my altimeter was 4,000 feet. Judglng by the speed at which I was passed by this bird, I should estimate that it must have been travelling at 90 mp.h.; which I consider to be quite a phenomenal speed for such a large bird at that high altitude.

Yours faithfully,

OWEN CATHCART-JONES,

Lieut. H.M.S. Courageous, at Skiathos, Greece, July 22.

which prompted Mr Seton Gordon, from the Isle of Skye, to reply:

Sir,

The letter from Lieutenant Owen Cathcart-Jones in The Times of July 27 which describes the great speed of a golden eagle in flight is of interest to me, as I have for some time believed the eagle to be one of the fastest birds. On one occasion I satisfied myself that an eagle was travelling at a good 120 miles an hour - probably much more -but then the bird was rushing earthward from a considerable height, and Lieutenant Owen Cathcart-Jones's bird was apparently on a level course. Little is definitely known even to-day as to the maximum speed any bird is capable of. Not so long ago a senior officer of H.M.S. Hood told us that when the Hood was steaming 34 miles an hour into a 15-mile-an-hour wind a formation of guillemots had no difficulty in forging ahead and crossing the vessel's bows. This interesting record shows that even the humble guillemot is capable of an air speed of well over 50 miles an hour, so a speed of 90 m.p.h. is not surprising in a bird of the wing power of a golden eagle.

I am, &c.,

During this time, he met Audrey, the wife of Captain Hugh Fitzherbert Bloxham, late of the Indian Army, then a Colonial Office official in the Prison Department at Hong Kong. Hugh and Audrey had married in St John's Cathedral, Hong Kong, on 6 August 1925.

Clearly Owen and Audrey got along rather well, and in November, 1927, their daughter Imogen was born.

Hugh duly sued Audrey for divorce in May 1928, "on the ground of her adultery, at the Hotel Savoy, Hong Kong, with Lieutenant Owen Cathcart-Jones, of the Royal Marines." The petition was uncontested.

On 12 Aug 1929 in Malta, Audrey had a son, Anthony.

"He established a reputation as a forceful and daring pilot, and one of his escapades became the talk of the Fleet; on 22 Aug 1929 he was on exercises with the Fleet and loaded his plane with a large packet of "service brown" toilet paper intending to drop it on H.M.S. Revenge which should have been last in the line. Unfortunately the C-in-C had inverted the line and he dropped the "bumph" very accurately on the Flagship, H.M.S. Queen Elizabeth. His Flycatcher aircraft was clearly numbered "7" and the Captain of H.M.S. Courageous was called to the Flagship on return to harbour to explain. Cathcart-Jones duly appeared before the Admiral with his reasons in writing [he made up some nonsense about it acting as a 'sighter' for actual bombs] and had to be on his best behaviour for some time."

On 26 November 1929 he made the first ever night deck landing in a fighter aircraft, flying a Fairey Flycatcher from H.M.S Courageous.

"It is a reminder of our one time presence in the Middle East that his record shows his Flight carrying out patrols in Palestine, and the Courageous Flights being shore based at Gaza and Aboukir in 1929 during the 'Civil War'.

During his Fleet Air Arm service he became very friendly with a wealthy Naval Officer, Glen Kidston, with a similar passion for flying. Kidston was himself leaving the Navy and Cathcart-Jones decided that it was time to do likewise and to transfer his interests entirely to civil flying. He went on to half pay on 17 Febuary 1930 [for 6 months], joined National Flying Services Ltd. and never returned to the Service.

Audrey, by then aged 28, with Imogen (aged 2) and Anthony (aged 1) sailed from Brisbane to Plymouth on the P&O steamship Ballarat, arriving there on 21 Jan 1930.

On 21 April 1930, National Flying Services held their first display at Hanworth Park; Owen provided the finale by bombing a level crossing to bits. However, the meeting was not a success; "for some reason N.F.S. shows do not appeal to the average private owner" and crowds were poor.

In September 1931 he flew a D.H. Puss Moth, with Audrey as passenger, in the Deauville-Cannes Air Rally. After lunch and a gala dinner, they flew on to Cannes, despite a forced landing in the Alps when the fuel pipe and filter were found to be blocked with sand.

By the following May (1932), business was better; "taxi work is now on the increase and the N.F.S. pilots have been kept busy flying to places as widely separated as Plymouth and Berlin". Owen piloted G-ABTZ, a Stinson Junior belonging to Mr. E James, on several flights. On 31 July 1932, Audrey went on a conducted tour organised by NFS, of "eight Moths, one Bluebird and one Alfa Romeo", to Ostend.

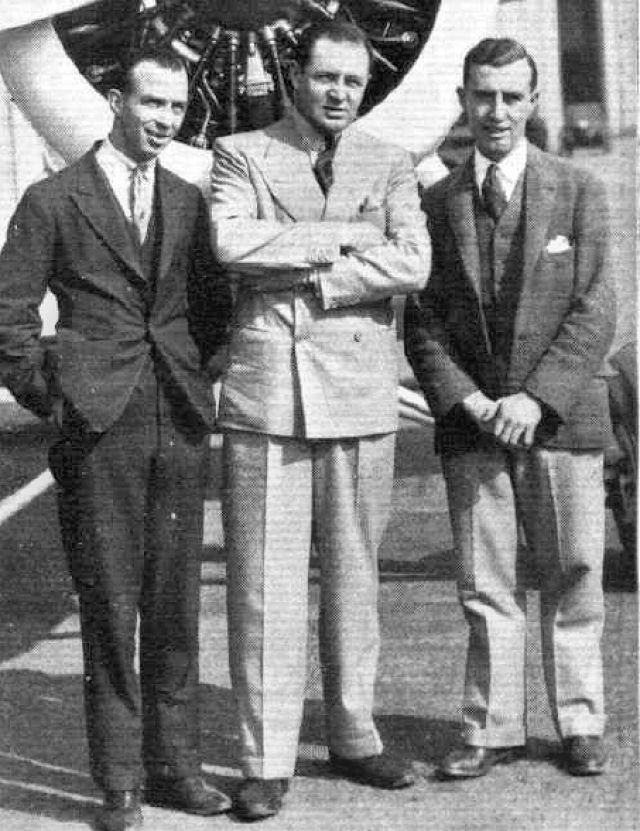

Owen and Audrey lived in Tudor Court, Hanworth, London until 1934, but then Owen moved out, leaving her and the two children, who relocated to Wavenden, Bucks. In company with Kidston he broke 8 World records for long distance flights in 1934, including England to South Africa in a Lockheed Vega:

but Glen (centre) was killed in an air crash shortly afterwards.

Owen also came 6th in the 2nd Morning Post Cross-country Air Race on 6 June 1933, and competed in the King's Cup in 1934 (finishing 9th) and 1935 (when he came a creditable 3rd).

Here he is, wandering around waiting to take-off, and taking a pylon in the final of the King's Cup 1934:

His real moment of glory was to co-pilot with Ken Waller the specially built D.H. Comet in the 1934 McRobertson England to Australia Centenary air race, in which they were awarded third prize in the Speed Handicap. On arrival they immediately turned round and flew back to England and established a record for the round trip.

Originally, he had teamed up with Miss Marsinah Neison in a Lockheed Altair (or Vega), "placed at their disposal by the builders", or possibly a Northrop Delta. However, nothing came of this.

He certainly wasn't first choice as Comet pilot - Bernard Rubin, the owner and intended pilot of the aeroplane, fell ill and originally nominated as substitute Mr Smirnoff 'the well-known Dutch pilot' on October 1st, and then only on October 5th (2 weeks before the race) 'finally and irrevocably' decided it should be Owen who accompanied Ken Waller. Three weeks before the Race, Owen had "never heard of Mr Rubin or Mr Waller", but apparently Marsinah said "Seajay, why don't you try and take Rubin's place?" Owen considered this a "most sporting action" on her part, but this meant that he had very little time to familiarise himself with the notoriously-tricky aeroplane.

After the return trip from Australia, Owen said "We have averaged 10 hours' flying every day, and covered approximately 2,200 miles a day. We wanted to make this flight back not so much as a speed flight, but as a flight which could be copied for commercial purposes. We have flown only by day, and have had time to sleep, eat, and wash. From the commercial point of view I think there is no reason why there should not be a service between Melbourne and England on similar times to those we have taken, certainly for the carrying of mails.

People in the Colonies were very anxious to have their letters quickly and to have air-mail services covering the distance in so short a time. We had one nasty moment at Allahabad, when we had trouble with two of the cylinders, but the Mollisons came to the rescue and lent us spare parts - a very sporting action. We were greatly disappointed by the delay at Athens owing to bad weather conditions, which prevented us from getting to Lympne yesterday."

Messages of congratulations included this one: "The Duke of Gloucester directs me to congratulate you both on a magnificent double flight - Private Secretary, Duke of Gloucester.

However, even while he was away, the law was after him: "ENGLAND-AUSTRALIA AIR PILOT SUMMONED. Flight Lieutenant Owen Cathcart Jones, of the Naval and Military Club, Piccadilly. who is taking part in the air race to Australia, was summoned at Bow Street Court yesterday, on a charge of using a motor-car with an expired Road Fund licence. He did not appear, and on being informed that Lieutenant Jones was one of the competitors in the England-Australia race, Mr Dummett adjourned the summons sine die."

In 4 April 1935, several visitors arrived by air for the Norfolk and Norwich Annual Dinner, including " Lt. O. Cathcart-Jones and Miss M. Neison in a Puss Moth".

He published his "Aviation Memoirs" in 1935; "... breezy, light and interesting... the book is unusually well illustrated, with photographs which Mr. Cathcart Jones has collected or taken himself, and many of these photographs are extremely graphic and educative." Interestingly, Owen rather neglects to mention anything about his wife and children.

In 1935, Ken Waller got annoyed with him for something he said in this book that Ken felt "reflected on his courage and ability as a pilot", and even went to court over it. Owen replied that "that was the last thing he intended, as Mr. Waller and he had been, and still were, very good friends", which seemed to settle the matter.

Reading the memoirs, I can only assume this was the passage where, having got themselves lost in bad visibility over Arabia during the Race, Owen says that "little did I know that Ken was on the point of asking me to dive the machine into the ground and get it all over rather than face the possibility of running out of petrol, forced landing in the sand, where we certainly would have smashed the machine, and then lie there slowly dying without means of help."

In fact, Owen's is a rather bland account of their two-way trip, and at one point Owen credits Ken with a 'marvellous achievement'; "Ken, under great difficulties, made a superb landing".

Also in 1935, he drove a 4.5 litre Lagonda Rapide in the Monte Carlo Motor Rally, starting from Stavanger in Norway. He was the first competitor to arrive in Monte Carlo, and was thought to have a good chance of winning the first prize, but was eventually placed 34th. His 'second-in-command' was a Miss Marsinah Neison, "one of the very few women to hold a 'B' licence for aircraft".

Owen and Marsinah got up to quite a few things together:

Beatrice Marsinah Neison, b. 3 Dec 1912 in Reigate. She gained her RAeC certificate at National Flying Services, Hanworth on the 11 Jan 1932, and passed the night-flying test in September.

Owen says of her "a young commercial pilot came to me for some advanced flying instructions, and I was very much impressed with the exceptional ability shown by her. Miss Marsinah Neison was the youngest girl pilot to get the coveted 'B' commercial pilot's licence. She qualified for it at the age of nineteen." He reckoned "there was very little I could teach her... I decided that her abilities were far too high to waste, and asked her to join me in any free-lance air charter work in which we could combine".

I'm not suggesting anything untoward, you understand...

In November 1933, she was trying to raise finance for a solo flight to Australia in a Comper Mouse, to beat the record held at the time by CTP Ulm, but never did.

Here she is, ready to go:

She sailed to California in May 1936, to visit her friend 'Russell Pratt', (sounds like an assumed name to me...) and to New York in July 1937. She married Hart Lyman Stebbins of New York 'very quietly' in London in December 1937, (they appear in the 'New York Social Register', whatever that means, for 1941), then Angus MacKinnon in July 1947. She died 29 April 1997 in Hampshire (England).

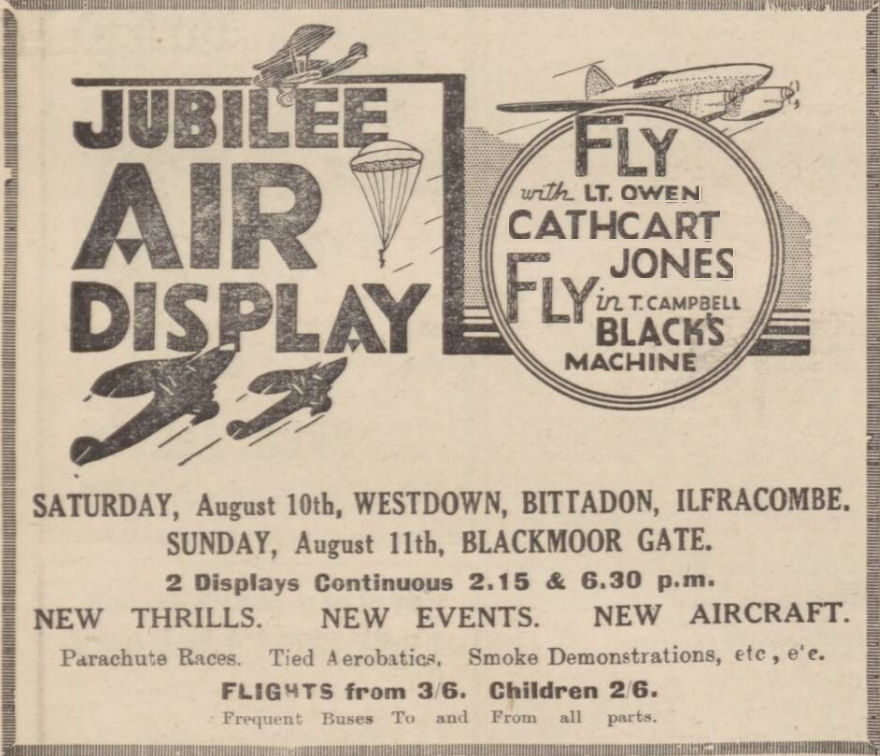

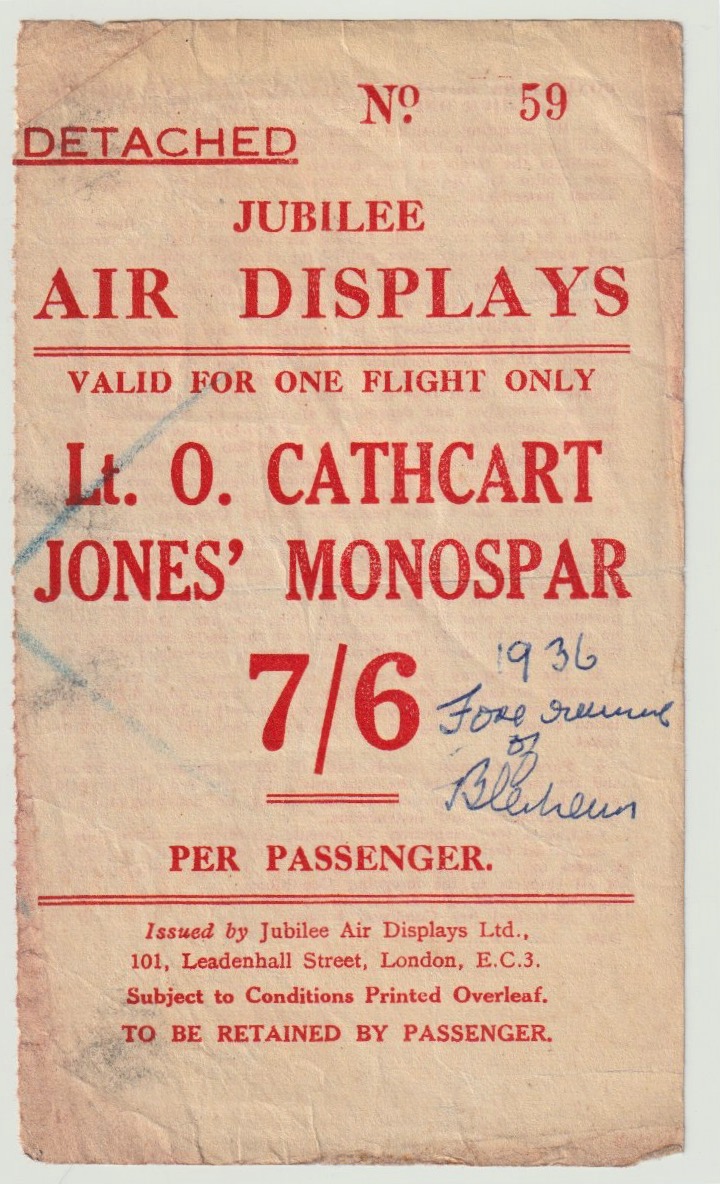

Anyway, Owen was by now pretty well-known; in May 1935, for example, he, Mrs Mollison (Amy Johnson), Tom Campbell Black, and other aviators took part in a 'Mock Trial', in aid of King Edward's Hospital Fund for London, at the London School of Economics; they were charged with 'Making the world too small'. The following August, he was chief pilot in the 'Jubilee Air Display', also with Tom Campbell Black.

via Joss Mullinger

via Joss Mullinger"Lieut. Owen Cathcart-Jones and Mr. T. Campbell Black, two of the keenest rival prize-winning pilots in the great England-Australia Air Race last year, are combining in a brilliant partnership to take a leading part in the Jubilee Air Display which will be given at Home Farm, Tehidy, Camborne, Thursday, August 15th. 2.15 till dark. The display which is visiting no fewer than 180 centres throughout Great Britain during the summer months, has been specially planned to provide a striking demonstration of the supremacy of British modern commercial aircraft and the unrivalled skill of British pilots. Public interest in aviation has never been more keen than it is at the present moment."

Don't be fooled into thinking you might have flown in the D.H. Comet, though - Owen flew passengers in a four-seat G.A.L. Monospar, and Tom took them up in an Avro Cadet, a rather pedestrian trainer.

On 31 July 1935, Owen advertised, again in The Times: "Mr Owen Cathcart-Jones requires sponsor to finance building world's fastest commercial aeroplane for nine special long-distance record flights in 1936-7 showing profitable return."

Nothing came of this either...

By December that year, however, Owen was banned from flying in Argentina because of his 'stunts'near a military aerodrome; the following April, his aeroplane was impounded by the Austrian authorities and he had to make his own way back home via Cannes.

Gigi Jakobs tells me that "I came across his name in divorce proceedings for Robin W.G. Stephens and Phyllis Gwendlen (nee Townshend) Fletcher. They started divorce proceedings in late 1936 because, according to Stephens, his wife had committed adultery with Cathcart Jones from Dec 1935 to May 1936."

26 Jan 1937

"Owen Cathcart Jones, the well-known airman, of Grosvenor Street, London, failed to appear at his first meeting of creditors at the London Bankruptcy Court to-day. The assistant official receiver stated fhat the debtor had failed to surrender under the proceedings. A distress was levied at his flat last December, and goods sold in January. A representative of the petitioning creditor said that the debtor took an aeroplane to South America for demonstration purposes. The debtor sold the machine and failed to account for the proceedings, and a judgment for £660 had been obtained against him. Mr Newman said that the debtor in August last was alleged to have landed in Czechoslovakia with two Spanish Nationals, and subsequently disappeared. Whether he is in Spain or not I don't know." said Newman, "but I believe he was in this country December 22 last." The case was left the hands of the Official Receiver as trustee."

The bankrupcy hearing was first delayed, then postponed indefinitely; Owen didn't turn up for any of the meetings.

He somehow became an instructor at the London Air Park Flying Club at Hanworth, an elite government-subsidized club for wealthy patrons. His fellow-instructors included David Llewellyn and Ken Waller.

Five years later, he was, somehow, a Squadron Leader in the Royal Canadian Air Force:

"In March of 1942 he was posted to Western Air Command Headquarters, but nothing is recorded in the WAC HQ diary to confirm this or indicate duties. He was then ‘Posted to ABS’ (Absent), 29 April 1942. It appears that he had gone AWOL (Absent Without Leave), as the diary of Headquarters, Western Air Command, under date of 6 July 1942, read in part, ‘Squadron Leader O.Cathcart-Jones who has been AWL for some time, returned from California to this Headquarters under escort.’ He is then shown as taken on strength of Western Air Command Headquarters, 6 July 1942. Two months later, he was ‘Retired’ from the RCAF”.

Hugh Halliday fills in some background:

"He was living in Mexico City in April 1940 when he applied to the RCAF and was duly commissioned in that force on 16 May 1940 (Pilot Officer, simultaneous promotion to Flight Lieutenant). He was assigned to the Air Member for Operations and Training, AFHQ, and performed well enough that he was promoted to Squadron Leader, 1 June 1941. The timing of this suggests (but I cannot prove it) that he was advanced in rank to give him more credibility with American authorities.

In April 1941 he was sent to California on temporary duty as Special Advisor to Warner Brothers for the film “Captains of the Clouds”. The RCAF paid him a special allowance of $ 10.00 a day for the time he was there. He seems to have considered California a bit of a “hardship posting” because of high costs and a depreciated Canadian dollar. He nevertheless wrote to people at AFHQ (Ottawa) on Warner Brothers stationery, at one point urging that he not be forgotten when operational postings were distributed. As of 20 February 1942, Hal Wallis (Director of the film) was effusive in his praise of Cathcart-Jones both in production and publicity preparation. His services with Warner Brothers apparently ended that day.

On 4 March 1942 he reported back to the RCAF on posting to Western Air Command Headquarters (Victoria, British Columbia). About a month later he was advised that he was to be posted to Station Alliford Bay as Operations Officer. A remote station in the Queen Charlotte Islands, it might nevertheless have been deemed to be in a zone of potential intense operations, given the panic that had engulfed the West Coast following the opening of the Pacific War. Cathcart-Jones would have nothing to do with it. He pleaded personal difficulties – privately he stated that he regarded Alliford Bay as a backwater – and he argued for assignment to Seattle as a Liaison Officer. On 27 April 1942, Group Captain A.D. Hull (WAC Headquarters), having interviewed Cathcart-Jones, wrote, “Squadron Leader Cathcart-Jones has undoubtedly ability. However, he appears to put his personal affairs before the Service. Should be closely supervised on new posting and given an opportunity to prove his initiative and worth.”

The same day (27 April 1942) he was issued a travel warrant to travel from Victoria to Vancouver and thence to Alliford Bay. By then he had cleared out his Victoria apartment and disposed of his books. He took the boat to Vancouver. On 28 April 1942 he crossed the border into the United States, in uniform, stating that he was on RCAF duty to the Fourth Interception Command, and that he was waiting for orders from Ottawa. He then hastened on to Hollywood.

On 29 April 1942 he wrote to Western Air Command Headquarters, submitting a resignation from the RCAF. Since he was already a deserter, the “resignation” was not accepted. In June 1942 he was arrested by American authorities, charged with having made false and misleading statements on entering the United States. He sent a message to WAC, asking that confirmation be sent that he was in California on RCAF Liaison Duty. This, of course, could not be provided (one is struck by the man’s sheer cheek). He was returned under arrest to Canada, reporting back to WAC Headquarters, and his case reviewed in detail on the 9th. Among the issues disputed were his debts ($ 884.09) and whether he should be “retired” or be allowed to resign his commission (his preference). He was retired. It was deemed that a General Court Martial for an AWOL case was “over the top” – he just was not worth it. He had not been paid since the day he went AWOL."

During his time with the RCAF he designed a board game, for which he did all the artwork; he was then involved in The Movies (Technical Director, and a 30-second appearance as 'Chief Flying Instructor' in 'Captain of the Clouds', of which Flight said " it is a first-class production in almost every respect" ).

See the excellent article on Vintage Wings of Canada's website.

He then got mixed up in some tawdry goings-on with Errol Flynn and a Miss Peggy Satterlee..

"This painting was done by Squadron Leader Owen Cathcart- Jones when he was an advisor on the movie 'Captains of the Clouds'. He also played a part in the movie. The painting shows the Hudsons Bay Co. trading post where the movie was filmed. When my father-in-law was ten years old, Cathcart-Jones gave him this lovely painting."

with thanks to http://relicsandtales.blogspot.com

He eventually bought a ranch to raise polo ponies, and became President of the Polo Club in Santa Barbara.

His daughter Imogen married John Otis Thayer (from Boston, Massachusetts) in September 1947. She was described as 'the daughter of Mrs A Cathcart-Jones of Wavedon, Bletchley, Buckinghamshire'.

Audrey died in 1962; her son Anthony in 2005.

In 1981, he wrote to 'Flight' "I had a bad accident at polo when I was knocked from my horse and fell on my head, but I am now almost completely recovered and back playing polo again."

Owen died February 1986, in California, aged 85.

Postscript

Imogen's son David actually met him: "Owen lived at 305 San Ysidro Rd., in Montecito. His ranch was about 4 acres at the end of a long driveway that passed through avocado orchards owned by the people who lived down on the road. It's been sub-divided and developed.

Some years ago, I walked up the driveway to discover that his house had been replaced by a large, pink, stucco hacienda and there's a second house, next-door, where his riding ring was. The avocado orchards down by San Ysidro Rd., are gone, too.Owen's sixth wife, and widow sold the place and moved to La Jolla a couple of years after he died. She died three or four years ago.

Imogen was reconnected with her father in the early 50s - he came to visit in 1952 and they wrote and phoned, after that.In the summer of 1965, my parents and their five kids drove out to Montecito, in a camper, and spent about a week at Owen's, just before he married his sixth ? wife, Pat, in August 1965.The following summer, 1966, I went out to visit him for two weeks, and was stranded in Montecito, for the whole summer, because of an airline mechanics strike which grounded the major airlines for 50+ days!It was great fun. My grandfather had to put me on the Continental Trailways bus, in September, to get me back to New York, in time for the first day of school.Owen had a second son, Colin, with his wife, Elizabeth Toomey, who he wooed away from her husband, in Buenos Aires, in 1936. She was married to a Mr. Waterman, who was, according to my grandfather's widow, Pat, the heir to the Waterman ink company. They married and had a son, in England, and came to NY soon after the boy was born. Evidently, in NY, he got involved with Marsinah Niesen, who was there and married to a Mr. Stebbins, and my grandfather walked out on Bette, leaving poor Bette to raise Colin in Queens, NY, with the help of her parents! She got no support from Owen.We have a January 1939 letter, from Colin's mother to my grandmother, Audrey, with her reaction to the news that Owen and my grandmother had not actually been divorced, though we do have a "Deed of Separation" which, I guess, is the precursor to divorce, in England.Bette Toomey Cathcart Jones had written to my grandmother for an affidavit of divorce so that she could proceed with her divorce from Owen. We have my grandmother's draft of the letter that she sent to Bette that prompted this response and my grandmotherher mentions Marsinah as one of the principals in her separation from Owen.Colin CJ died last January [2013]. We had Owen's passport with his and Bette Toomey's photos and Colin's name written in. I looked him up on the Internet and telephoned. We planned to meet but never got the chance. I spoke to him, just a year ago, on his birthday. November 13th." -

Cazalet, Robert George

Capt Robert George Cazalet  photo: 1927, aged 35

photo: 1927, aged 35 -

Comper, Nicholas

Flt-Lt Nicholas Comper

in 1916, aged 19

in 1916, aged 19lecturer at the Cranwell Engineering Laboratory, ex Cambridge University.

Designer of the Comper Swift; died in 1939 after a practical joke went wrong

-

Cook, Arthur Harry

Mr Arthur Harry Cook

in 1932, aged 23

in 1932, aged 23b. 29 May 1909 in Bletchley, Bucks; educated at Bletchley Grammar.

In 1932, worked for Beacon Brushes Ltd, Bletchley; apparently, brush-making is Bletchley's oldest large-scale industry and Beacon Brushes was formed in 1926 by 'Jack Cook and his sons'. See http://www.discovermiltonkeynes.co.uk

Arthur's father was called Arthur John Dennis Cook, but anyway by 1943 our Arthur was 'Works Manager and Joint Managing Director' of the firm, based at Church Farm, Wavendon, Bucks. Which is near Bletchley (that's enough mentions of Bletchley).

Air Transport Auxiliary in WWII

d. 1980

-

David, Edward Hugh Markham

Flt-Lt Edward Hugh Markham David I think this must be Flt-Lt (later Sqn Ldr, Wing Cmdr from 1939, Grp Capt, CBE) Edward Hugh Markham David, who served in the Navy in WWI, as a cadet at Osborne in 1914 and Dartmouth, and a midshipman in the 'St Vincent', 'Whiteley', and 'Revenge'. He was one the very first tranche who trained at RAF Cranwell when it opened in 1920.

b. 10 Jan 1901 in Monmouth, he was posted to Iraq in 1921-25 and Aden in 1932-4, then became Adjutant of 604 (County of Middlesex) Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force.

DFC in September 1941; retired and moved to Malta after WWII; his daughter Diana Elizabeth Markham married in 1952.

d. 1957

-

de Havilland, Geoffrey

Capt (later Sir) Geoffrey de Havilland O.M. K.B.E A.F.C Hon.F.R.Ae.S

1911, aged 29

1911, aged 29  1936, aged 54

1936, aged 54Geoffrey de Havilland - Wikipedia has his story -

de Havilland, Geoffrey Raul

Mr Geoffrey Raul de Havilland

1936

1936Geoffrey Junior, aka 'Young D.H.' born in 1910 and learnt to fly at Stag Lane at a tender age. Took over as chief test pilot at de Havillands when Bob Waight was killed.

Second Brit to fly a jet-propelled aircraft on its first flight, the Vampire in 1943. Killed when the second DH108 Swallow broke up and crashed in the Thames estuary in 1946.

Flight 18th April 1946

As a test pilot young D.H., as he is universally called,has not an exceptionally long history. He took over the chief test pilot's position in October, 1937, when R. J. Waight unfortunately lost his life on the T.K.4. Being, however, the son of his illustrious father, Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, who designed, built and test flew his own aircraft from 1911 onwards, young Geoffrey can be said to have been ''in the industry'' from the very cradle. It is not generally known that Sir Geoffrey took his R.Ae.C. ticket No. 53 in February, 1911, on the second machine of his own design and construction, and that he has made many of the first flights on new D.H. types right up to the Moth Minor in 1938.

Geoffrey's first flight is lost in the dim past, but certain it is that at the tender age of six he was flying with father at Hendon in a D.H. 6 (also known as the Clutching Hand). When 18 years of age he left school and came to de Havillands as a premium apprentice for 4 years and learnt to fly on Moths at the firm's reserve training school. After spending two years in the drawing office—much of the time being spent looking out of the windows envying the pilots—he joined the Air Operating Company, who were doing a lot of air survey work in South Africa. This, however, gave him but very little flying, and at the end of six months, he came back to England to become a flying instructor to the D.H. Technical School. The aircraft were wooden Moths built by the students. In 1929 he took his B licence; a very simple business in those days. Some 20 or 30 hours' solo flying, a little cross-country work, a simple "Met" exam, and about one hour's night flying at Croydon was sufficient to qualify.

In 1934 Capt. Hubert Broad was chief test pilot of de Havillands, and Bob Waight looked after the production side. There was so much work, however, that Geoffrey was given the opportunity to lend a hand testing Tiger Moths, Dragons, Rapides, Express Air Liners, and Hornet Moths.

Broad left the company in 1935 and Waight took over, starting, with the Dragonfly and later the Albatross. It was during the period when the prototype Albatross was going through its development flying that Waight lost his life, and de Havilland took over as chief test pilot. Nobody could have taken on a more interesting or more complex job because the Albatross was completely experimental from tip to tail. Engines were new, construction was new, and the layout was extremely advanced.

He had a curious experience on the Albatross. While its strength was ample for all flying loads, some unfortunate drilling had weakened the fuselage under ground loads, and shortly after landing from a test flight the machine broke in halves on the ground.

When war broke out lie was busy testing Oxfords and Flamingoes, but when things became desperate at the time of the Battle of Britain, de Havillands did a big job doing emergency repairs to shot-up Hurricanes.

Dick Reynell of Hawkers came over and gave Geoffrey the "know how" on Hurricanes. A little later Dick went out on operations with his old squadron (No. 43) and was, unfortunately, shot down.' He was an excellent test pilot and a gallant gentleman.

Improvised Runway

Geoffrey flew the first Mosquito at Hatfield on November 21st, 1940, but he is more proud of the first flight of the prototype Mosquito fighter. This was built at a dispersal factory with no airfield. To save some six week's wasted time in transport and re-erection at Hatfield, Geoffrey used local fields by having bridges built over ditches to give him a 450yd run for take-off, and then flew the fighter to Hatfield.

He is, of course, one of the only two men in Britain to have made first flights on jet-propelled aircraft. The Vampire was flown for the first time on September 21st, 1943, but Geoffrey had already flown the Gloster E.28 at Farnborough. The first airing of the Vampire proved it to be a tribute to the D.H. design and aerodynamics staff, as it behaved almost exactly as they had forecast. There was, however, somewhat of an aileron overbalance which limited the speed to 250 m.p.h. and a rather severe tip stall.

Geoffrey de Havilland had made a number of investigation flights on Mosquitoes for compressibility effects, but on the Vampire he has done extensive work. The Vampire, under the effects of compressibility, executes a series of sudden high-speed stalls: the path of the machine is similar to an artist's conception of a streak of lightning, and unless the pilot is strapped-in tightly he is likely to be knocked out by hitting the cockpit roof.

Geoffrey, with another pilot, has flown the Vampire in tight formation at over 500 m.p.h., and to investigate snaking, which is causing considerable trouble on most jet aircraft, he has flown the Vampire with rudder locked.

Like most of the test pilots, he is living on borrowed time, they having at some stage of their careers had close shaves. Strangely enough, Geoffrey's nearest go was on about the mildest type he ever flew. It was the first production Moth Minor. The prototype had completed its spinning tests, and the same tests on the production model appeared to be only a matter of form. He was flying with John Cunningham (now Group Capt., D.S.O.,D.F.C., and test pilot for the D.H. engine division) at the time. The Minor was put into a spin at 5-6,oooft, but after it had failed to come out in five turns and the engine had stopped, a panic decision was made to abandon ship.

Test-flying a Hurricane, too, almost saw him off. This particular aircraft had had a gruelling time in the Battle of Britain, and the whole canopy came off at 4,000ft.hitting him in the face as it blew backwards. At first blind through the amount of blood in his eyes, he flew more by instinct than anything else until he found he could get a little relief by holding his face close to the instrument board. The blood dispersed a little and he was able to land through what appeared to be a thick yellow haze. He wears the scars across his nose to this day, and there was a terrible moment during that flight when he thought he was really blind.

On another occasion the oxygen bottle contained only compressed air, and the effects from this were at first blamed on the previous night's party.

At the other end of the scale was the test of the T.K.5, a tail-first aircraft built by the technical school. Impecunious at the time, Geoffrey had already mortgaged the bonus for the first flight. Imagine his consternation then when, after roaring the whole length of Hatfield airfield, the machine showed no sign of lifting. The forward elevator was ineffective. The T.K.5 never did fly and was finally abandoned.

In the days of peace before the war Geoffrey de Havilland was to be seen at all the air meetings and twice finished 4th in the King's Cup Race flying the TK1 and TK2.

-

de Havilland, Peter Jason

Mr Peter Jason de Havilland  1931, aged 18

1931, aged 18middle son of Geoffrey; both his brothers were killed in flying accidents, but he survived and published his father's autobiography in 1979 -

Edwards, Hugh Robert Arthur

P/O (later F/O, Flt-Lt) Hugh Robert Arthur Edwards  1929, aged 23

1929, aged 23'Jumbo', the famous Oxford rowing coach, younger brother of Cecil

His grand-daughter's husband Gavin has written Jumbo's story, in four parts, starting here:

https://heartheboatsing.com/2020/02/17/jumbo-edwards-oarsman-coach-and-raf-pilot-part-i/

-

Gardner, Charles Exton

Mr Charles Exton Gardner  1931, aged 25

1931, aged 25Aeronautical engineer 'with his own aerodrome at home in Surrey'. Always nice to have.

"Flew to India [in 1936] to compete in the Viceroy's Cup Race"

-

Healy, Lewin Edward Alton

Flt-Lt Lewin Edward Alton Healy RAF Cranwell, 1922. Twice mentioned in dispatches.

-

Henshaw, Alexander Adolphus Dumfries

Mr Alexander Adolphus Dumfries Henshaw  1932, aged 20

1932, aged 20b. 7th November, 1912.

The extraordinary Mr Spitfire. Leant to fly in (of all places) Skegness. "After 25 hours solo bought a Comper Swift and in the 1933 King's Cup Race won the Siddley Trophy with it." In 1936, still the youngest competitor in the race.

d. 24th February, 2007

-

Hope, Walter Laurence

Capt Walter Laurence 'Wally' Hope  1917, when a 2nd Lieut in the RFC, aged 20

1917, when a 2nd Lieut in the RFC, aged 20 1928, aged 31

1928, aged 31Technical director of Air Freight.

b. 9 Nov 1897 in Walton, Liverpool

Aged 18, and described as a "trick-cyclist", he was summoned in 1915 for committing a breach of the Realms Act by taking a photograph of one of his Majesty's ships at Barrow; he pleaded not guilty, admitted that he was carrying a camera, and was fined £5.

A close friend of Bert Hinkler, he made an extensive search over the Alps at his own expense when Bert went missing on his fatal flight in 1934, but then sued the Daily Mirror when they published their hair-raising account of his exploits, "Captain Hope's Ordeal in the Alps". He said there was "not one word of truth in it."

m. 1920 Marjory [Stone]

Three-time winner of the King's Cup Race (1927, 1928 and 1932)

In the 1926 King's Cup race, "he had to descend at Oxford while racing for home in the last lap with a small “airlock" in his petrol pipe, which effectually put his tiny Moth machine out of the running. He landed in a small field - so small that he found it impossible take off again when his minor trouble had been rectified without pushing his plane through three fields to a broader stretch of country, where he could rise. By this time it was so late that he decided that would abandon the race and go on at his leisure to Hendon.

Interviewed at his home in Hendon yesterday, Mr. Hope said: “The only thing that I am really disappointed about is that I feel sure that if this trifling mishap had not occurred I should most certainly have won. For three laps I was racing neck and neck with Captain Broad, with an aggregate speed equal to his - between 90 and 91 m.p.h." Daily Herald

At the end of the 1928 race, "Thinking all was over he proceeded to loop and stunt before landing, and having landed switched on his well known winning smile. Suddenly there was a terrific hooting, and Sir Francis McClean in his white Rolls-Royce came tearing across to tell Hope he had not crossed the finishing line... Within 30 seconds Hope was in the air again, discovered the finishing line, landed, and again switched on the winning smile fortissimo." C G Grey

Entered for the MacRobertson Race in 1934 (No 24) but didn't take part in the end.

m. 1954 Hilda L [Stone or Hunt]

d. Oct 1979 - Isle of Wight

-

Irwin, Angus Charles Stuart

Mr Angus Charles Stuart Irwin  1916, when a 2nd Lieut, Royal Irish Rifles, aged 18

1916, when a 2nd Lieut, Royal Irish Rifles, aged 18 1931

1931born in Motihari, India; educated at Marlborough and Sandhurst. RFC in WWI: 2 victories, but was then shot in the foot by a member of Richtoven's squadron.

Post-WWI, was "engaged in the estate business" (whatever that means).

-

Jackaman, Alfred Charles Morris

Mr Alfred Charles Morris Jackaman  1927, aged 23

1927, aged 23A civil engineer from Slough; in 1936 he and Marcel Desoutter decided that an airport at Gatwick might be a nice idea (it was, after all, "outside the London fog area").

He later married Australian-born Muriel Nora 'Cherry' Davies and they ended up near Sydney; he died in 1980, but she survived until 2011 - aged 101. see

http://www.smh.com.au/national/obituaries/love-and-duty-shaped-long-life-20110923-1kp9i.html

Page 1 of 3