|

Memories of the Aerial Circus

[Forester (Fred) Lindsley, having worked for Airspeed, went to work with Cobham in early 1935. He published some memories in an Australian magazine called 'Western Flyer' in the early 1990s, reproduced by the Brisbane Branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society in 1994. His son put these memories online recently, and I have included some of them here. You can read the full text at https://m.flickr.com/#/photos/63810556@N03/5810910124]

Part 1 - Down to Earth behind the scenes

In the so-called golden age of aviation, the 1930s, when entirely new aircraft appeared in rapid succession, and there was no general public awareness of a major war looming not too many years in the future, touring air displays were a popular spectacle.

Far and away the largest of the European enterprises was Sir Alan Cobham's Air Display which, under its initial title of National Aviation Day, commenced its first tour of Great Britain in 1932. I joined the organisation at the beginning of 1935, when the aircraft were undergoing their winter overhaul at Ford in Sussex.

The following year, 1936, the name was changed to C.W.A. Scott's Air Display, although most of the aircraft and personnel remained unchanged. The business name of the organisation was actually Trafalgar Advertising Ltd (and it was indeed a business) with its headquarters in a small and far from lavish office near Trafalgar Square in the heart of London.

The programmes the public got were very good, varied and slickly produced air displays, twice each day in the afternoon and evening. With British Summer Time it was light until after 10pm, and later still in the northern latitudes. I can remember being able to read a newspaper at midnight, near Thurso at the northern tip of Scotland.

The shows were also seven days per week. 'The Show Goes On' really meant something, because the name of the game was selling joy-riding.

|

The opening mass formation flight over the local town did not see an engine start up until every available seat for the flight had been sold - excepting the complimentary seat for the local Lord Mayor, beamingly oblivious that the pilot of the 'Giant Airliner' would cheerfully strangle the Mayor with his own heavy gold chain of Office. |

Tickets were sold in different colours at different prices, the Ringmaster M.C. at the microphone being singularly adept at guaging the optimum starting price for any locality. There were times when the Avro 504s were down to three shillings and sixpence. Towards the conclusion of the evening shows it was customary to reduce prices, the fundamental function of the display being to produce the maximum revenue before the public departed the flying field.

The aircraft loaders retained the public's tickets, for pilots were paid on a retainer plus ticket commission. At the end of the day, any sounds of disharmony could usually be traced to the balancing of money receipts with ticket returns.

Putting the Show on the Road

Behind these magnificent men in their flying machines, and notwithstanding the rather unimpressive office which kept tabs on activities (and was the post box for our mail), the whole enterprise was large and complex.

Months ahead there was a reconnaisance party which dealt with local authorities, advance publicity, and farmers. The utilisation of likely fields might be dependent on crops, hay - or the local annual Morris-dancers festival. This sort of thing could see us flying up to 200 miles between displays, and was hell on earth for the road transport people. They had to pack, travel overnight and set up well in advance of the first show. The store truck was always [having] a problem which, on short transits, usually delayed its morning departure. No matter how many likely spare gaskets we had in our tool-boxes, there was often a last-minute something that only the stores truck could supply.

Just prior to D-Day there was the advance party, led by a genial glad-hander named Jerry Hancock, who arranged hotels for the pilots and promised the farmer that he would make a fortune when he sold his paddock as a future airport (which at the time lacked the imposing grandeur of 'International'). Jerry also organised publicity posters, slides at cinemas and supplied photo blocks plus press handouts to local newspapers. Of which there were hundreds. One of my tedious chores (until discovering the art of delegation by flattery) was pasting the names of newspapers on each side of the Wolf sailplane's plywood fuselage, and unsticking these 10 feet long posters every evening.

For their own posters, no newspaper ever had any type less than 12 inches high.

On the display day there first arrived the screeners (a party of four, sometimes plus local casual labour) who put up the steel stanchions and incredible lengths of canvas, which prevented people from getting a free look from adjacent roads or public land. We also had two policemen, retired cops of immense solidity, who discouraged kids from tunnelling through hedges, and who established a rapid rapport with the local Constabulary, ensuring that motorists did not get free views by standing on the roofs of parked cars.

The 'loudspeaker van' was the centrepiece of the show, parked just inside the barrier wire by the ticket tent. The driver of this van was one of the hardest worked people on the show. He looked after the loudspeakers, constantly misbehaving microphones, the amplifier, the gramophone records and the charging of a massive array of batteries supplying public address power.

The Business Command Post was the 'Gate Van', almost impregnable and thief-proof because that is where the money was kept. A staff of four gentlemen could be kept extremely busy on a good day, selling entry tickets for people and cars.

Then there was the refuelling wagon with a team of two. In both 1935 and 1936 this was a huge Leyland six-wheel tanker supplied by National Benzol. All engines, vehicle or aircraft, as was frequently mentioned on the loudspeakers, ran on National Benzol. Free, of course. I have the recollection that some of the engines, the Jupiters and the Armstrong Siddeleys I think, had the carburettors jetted for 80-20 petrol benzol mix.

Wings and wheels, on the same gratis basis, were lubricated by Castrol in various grades. To minimise the quantity of reserve oil carried by the stores truck, Castrol in 4 gallon drums was delivered to each display site in vast quantities by the local depot, who also collected unused drums the next morning. These drums were stacked in pyramids, Castrol label to the fore, at the car promotions and at strategic places on the flight line. The public could actually see the superb unction being poured into aircraft in which they soon intended to fly. The Castrol Sales promotion team's confidence in their marketing technique was well justified.

There were also the franchisers, who were many and varied. They paid a fee and were free to make their own profits, transporting and erecting their own tents in their own transport. The major one was the canteen marquee which, by arrangement, had prices for staff more reaasonable than the sliding scale applied to the public. Other franchisers came and went, some only operating in a restricted locality, but the steadies werfe a museum of scale models, programme sellers and vendors of display souvenirs, like brochures.

With the exception of the fuel tanker, all transport in 1935 was supplied by Ford, and in 1936 by Vauxhall/Bedford. In each case those companies, with their local agencies, had an all-model motor show and sales promotion at every show.

Part 2 - Keeping Them Flying

From time to time, other itinerant joy riders would join our display, usually in particular areas like the British South Coast in the holiday season. If they ran into maintenance problems we might get a better acquaintance with Monospars, Short Scions, Klemms, the Handley Page W8B "Prince Henry" with two Rolls-Royce Eagle engines, and even a three-engined Armstrong-Whitworth Argosy amongst other types.

Relying on memory the aircraft in 1935 were: the Handley Page Clive (two 550hp Bristol Jupiters), Airspeed Ferry (two Gipsy II and an inverted Gipsy III on top), two Westland Wessex (three Armstrong Siddeley 5-cylinder Genet Majors), three 3-seater Avro Cadets (A/S 7-cylinder Genet Major), Tiger Moth (Gipsy Major), Avro Tutor (A/S Lynx) one Avro 504N (A/S Mongose), BAC Drone (Douglas Sprite converted motorcycle engine) and Schemp-Hirth 'Wolf' sailplane. This glider, aero-towed by one of the 504s, did quite vigorous aerobatic displays every day for two seasons, which is close to 700 aerobatic sessions for a wooden glider designed to the German strength requirements of 60 years ago. However, a bigger drawcard than the glider was the first appearance of the 'wingless wonder', the Type C30P Autogiro (7-cylinder Genet Major) flown by 'Crasher' Ashley. An underserved nickname, but he was a 'new boy', who had just gained his commercial licence.

In 1936 the organisation, and about 90 per cent of the personnel, was not much different to the previous year. The Clive had been retired after carrying 120,000 happy fare-paying passengers, and a not so happy me on one memorable occasion. Both the Wessexes and the Drone also rested from the rigours of touring. We got another Airspeed Ferry and the 1935 Ferry had its two outboard Gipsy IIs replaced with Gipsy Majors salvaged from a DH84 Dragon, which had ditched in the English Channel. We also got the 1936 star turn, a Flying Flea with a liquid cooled Ford 10 engine conversion, and, very briefly, before it set out for South Africa, a Hillson Praga. This Czech aircraft built under licence was unspinnable, and is worthy of some reconsideration today. The Praga engine, made under licence by Jowett Cars, was not very satisfactory.

Inside the wire, and sheltering from the sun or wind at one end or other of the flight line, was a most important person in the operations. The Time-Keeper. Most usually a young aviation enthusiast of some means, who could spare a few weeks before going to Uni or joining one of the aviation firms. For back-up there was 'Atlas' - of whom more anon. The time-keeper logged to the minute the take-off and landing times of all aircraft; a task demanding intense concentration on busy days. The purpose was serious. Pilots needed the time for their logbooks, and we needed times for the maintenance logbooks.

The display ringmaster, or MC, the man at the mike, was the golden-voiced Roy Arthur, the stage name of a theatrical pro who had trod the boards and made the big-time at the 'Little Twittering Colosseum'. Whenever even Roy's eloquence failed to move people in the direction of the ticket tent, his place would be taken by the Display Manager - who knew how to persuade Mrs. Bloggs to purchase a right of entry to the Giant Airliner. Whereupon, three other ladies would say to their husbands, "If that Sadie Bloggs flies in an aeroplane we will never hear the last of it". With the sluice gate satisfactorily open, Roy would again take over the mike.

The Manager could charm lobsters into joy-flights. He was never known to set foot in an aeroplane, his previous service in World War I as a kite balloon observer having apparently exhausted his capacity for enjoyment of airborne aviation.

Then there were the pilots, nearly all ex RFC or ex RAF short service commission. Extremely competent, as some of the paddocks used in Scotland and Ireland very nearly required a miniature railway to put them in perspective. There were mishaps, but in two years no fare-paying passenger was even scratched. Operations were intensive, By the end of the season the two Ferries had logged well over 10,000 flights with up to ten passengers at a time. While the flights were probably less than five minutes at a time, it is a lot of full-power take-offs and landings on fields which frequently left a lot to be desired.

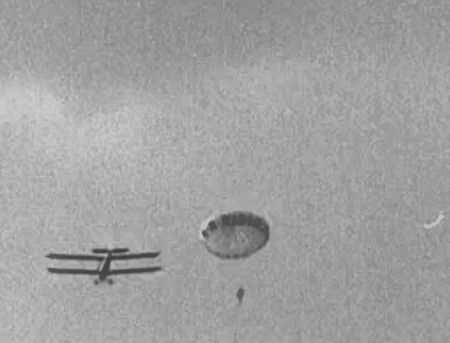

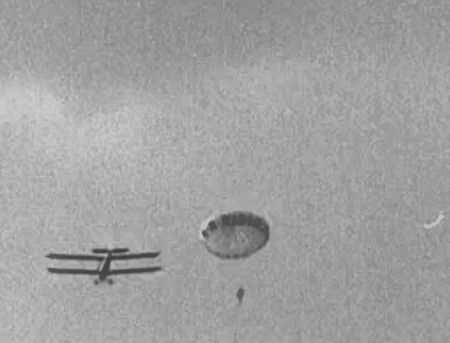

In 1935 there were two parachutists, Ivor Price and Naomi Heron-Maxwell, who did pull-off releases from two platforms at the rear outer interplane struts of the Clive. In 1936 Al Harris, who had done some of the jumps in 1935, did the parachuting from an Avro Cadet. He also did joy-riding in the Cadet too.

The engineering staff also featured ex-RAF members, but also included engineers who were on loan from Bristols and Armstrong Siddeley, and who were really excellent. They had all started on the bench, gone through manufacturing, the view room, the test beds and overseas service. Their ability to inform was superb; describing aspects of super-charging with a beer-soaked finger on a table top is a fine art.

Backing up the maintenance staff were the loader/cleaners, one per aircraft. The Avro 504s required ladders for passenger access. One of the important functions for a loader was to grab the wingtip of an incoming brakeless aircraft and turn it so that its tail was towards the crowd. The loader had to be particularly alert that excited disembarking passengers, mad keen to join their admiring friends, did not run into rotating propellers. One woman ran unscathed through the prop of a Short Scion at Weston-super-Mare, which proves that there was something to be said for the reduction gear on a Pobjoy engine.

Maybe, about twice a season, we would get an aircraft into a hangar. There is a vague memory of Joe King doing a solo flight to Blackpool on two engines so that we could change the upper engine on a Ferry. Otherwise, maintenance was distinctly an open air affair, rain or shine. Engines and undercarriages had a hard life. The Avro 504N wheels had plain bushes requiring greasing more than once on a busy day, and the stores truck carried a fair weight of spare bushes.

Most major spares were held back at base, Ford Airfield in Sussex. And also some other hibernating aircraft, such as the Blackburn Lincock, with an empty weight suggesting it was made of solid metal; stub winged C19 autogiros, out of favour due to their notorious ground resonance 'dance of death' and a DH9 with a Siddleye Puma engine which had been used in flight refuellling experiments. All in the care of an elderly faithful retainer.

.jpg)

From a remote outpost of the corporate empire there was sent a telegram asking the faithful retainer to ensure the first available passenger train carried northwards a spare tailskid for the Handley Page Clive - a large lump of ironmongery terminating with a heavy steel disc about the size of a very large soup plate.

Repeated journeys to the nearest railway station revealed no Passenger, Fish or Freight trains in any danger of exceeding their axle loading limits with what we needed. Expediency overcame protocol, and the aged retainer was phoned a message of some urgency. "Aah", he said, "so them things we have is tailskids, are they? Oi calls them draggers".

Part 3 - The Funny Side

The 1935 display, in July and after its tour of Ireland, split into two divisions. One with the Clive plus a Grunau Baby glider flown by Eric Collins, and the other tour with the Airspeed Ferry G-ABSI. In less than six months of the summer season 244 locations were visited, only sixteen of which were established airfields. A few places were two day events which meant four shows. There was just one day off, presumably due to weather. So, roughly speaking, I participated in around 340 displays during the first year. There were few towns that didn't get a display within walking distance, car ownership being sparse in a recovery period after a severe economic depression. The places visited ranged from Thurso in the north of Scotland to Penzance near Land's End in the south, and from Lowestoft in the east coast to Tralee in western Eire.

There was one break from circus tradition. The overture music on the public address system was not the standard 'Entry of the Gladiators'. It was a then equally popular march 'With Sword and Lance'. There was however a very firm adherence to long-standing circus tradition. We had comedy items, about five different routines which varied slightly. There were never more than two in the same show. Their timing would be altered as necessary - sometimes to divert the audiences at short notice, such as some lapse of expertise like a taxying mishap. Or the charming lady who flew the Wolf sailplane, Joan Meakin, taking advantage of thermals to cruise around without an engine. This drove the Manager into a state of near beserk rage. Nobody was going to purchase a flight in an aeroplane when they continued to witness a near miracle performed by a flying machine without an engine. Bring on the clowns, quick!

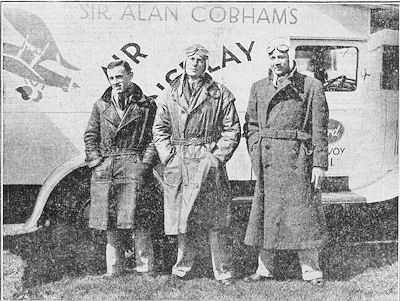

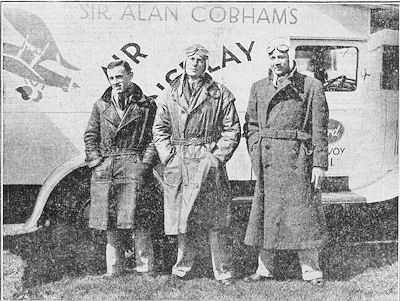

Martin Hearn, Geoff Tyson and Flt Lt H C Johnson in 1934

The comedy routines were masterminded by Martin Hearn who had done the wing walking in earlier years until it had been prohibited by the Air Ministry. He continued to do it in Eire and it was every bit as impressive as may be seen on Oshkosh videos today. Martin also ferried the Tiger between locations since Geoff Tyson had to ferry the Avro Tutor. Aidng and abetting Martin (apart from contributing piloots) were a droll Cornishman called Charly Craig, and a thick-set middle-aged dwarf from a theatrical casting agency, who insisted on being known by his stage name 'Atlas'. To strangers he preferred to be introduced as Mr. Atlas. The fourth comedy conspirator had been played the previous year by an engineer named Roy Bonner, who conspired that I should take over his part on the promise that he would explain to me the intricacies of master and articulated con-rods. So, twice a day, I became a drag queen, nerly half a century before coming out of the closet became prurient entertainment on TV. Martin Hearn said I was well suited because this absolute star part highlight of the display required agility, and the possibility of developing humour combined with the dim-witted misguided idealism of wanting to be an aircraft engineer. Routines are hard to explain in words. One of them was 'The Wedding'. The major prop was an open four seater bullnose Morris Cowley, very dilapidated. When Charly drove it from place to place he was often stopped by the police. The vehicle would emerge from the end of the field, driverless, because Charly was lying on the floor getting steering directions from the happy bridal couple sitting up on the folded hood at the rear. Martin in the top hat and me in the bridal gown playfully bashing Martin with the bouquet should his advances be too amorous. The vehicle stopped well outboard of the speaker van, with its starboard side towards the crowd and the man on the mike remonstrated about obstructions on a famous or future famous aerodrome. Charly would slide out of the left front seat, to appear as a grotesquely dressed yokel wanting the car and the bridal couple off his land. The man on the mike called for serious action and Geoff Tyson took off in the red and white chequered Tiger Moth.

.jpg)

There was much funny business and Charly pulled a revolver (loaded with blanks). His second shot was fired at point blank range into a large steel tray on the starboard running board filled with petrol-soaked rage. This produced a most impressive blaze with flames about six foot high and lots of smoke. I ran around to put it out by waving my skirt, exposing bright scarlet knickers, always good for a laugh, and from the speaker van ran Atlas wearing a policeman's hat and bearing a Pyrene fire extinguisher. With a few pumps of Pyrene, well publicised on the speakers, Atlas put the fire out in seconds. Extinguishing the fire was the signal for Geoff Tyson to start his flour bomb attacks, french chalk in paper bags. A twice a day demonstraion of low flying with the public never in the slightest danger. The bombing was combined with more funny business, running and cartwheeling over one another until the Tiger gave a quick blip on the throttle meaning bombs exhausted. Atlas got the gun and, with Charly at the wheel, chased the discomforted bridal couple off the end of the flight line. Clutching the gown around my waist, and air-cooling those scarlet bloomers, I could in those days do a forward running somersault every time the gun fired. It sounds a bit backwoods hick today but the crowds loved it and it was, of course, a magnificent advertisement for Pyrene fire extinguishers.

Geoff Tyson, who recently died at the age of eighty, after WWII attained some fame as the last pilot on the 10-3engined 'Princess' flying boat. We had occaasional visits from N.S. Norway who, together with Hessell Titman, had designed the Airspeed Ferry. In addition to seeing how the Ferries continued to stand up in service, Mr Norway was interested in all display activities. Some years later he became more famous with his first best-selling book 'The Pied Piper'. As a write he used his initial name, Nevil Shute. He also wrote 'Round the Bend', which features the air circuses and the comedy items in the opening chapters.

Part 4 - The Giant Airliner

.jpg)

'Giant Size' was a phrase much used by advertisers in the years before 'King Size' became a more vogue term to encourage the selling of marketing articles.

Thus, it came about in the 1930s that any aircraft with windows in the sides, like a Fox Moth, became an airliner, and if it had a fair few windows it was a 'Giant Airliner'. So the residents of any small township like Much Babbling-in-the-Bog would be eager to see, and perhaps equally eager to sample, the visitation of a large aeroplane which clearly ws intended to prove that their parish was a likely hub for all future air transportation within the British Isles.

The one and only Mark I Handley Page Clive, with its ability to get into and out of small but smooth paddocks, ideally lived up to the advance publicity. Built in 1928 as a troop-carrier conversion of the Hinaidi bomber, with a higher fuselage, it had commenced its civilian career in 1932 giving joy-rides with Sir Alan Cobham's National Air Day air displays. It was also used as a tanker aircraft in Sir Alan's flight refuelling experiments.

My acquaintance with the Clive started in January 1935. It was undergoing C of A overhaul together with the Airsped Ferry, my previous contruction experience on the latter having led an earlier foreman into persuading me to join him on the air display staff. The Clive had sixteen passenger seats, in the best vintage wickerwork. Although they had safety belts it is very doubtful if those seats, and their floor attachments, would come within cooee of modern airworthiness strength requirements. Nevertheless the Clive in four joyriding seasons carried 120,000 passengers without a scratch. Even if it carried a full load each time, which is far from correct, it works out to about 11 take-offs and landings per operatng day on that curious landing gear.

The Clive was withdrawn from service at the end of the 1935 season.

A Different sort of Straight and Level

Within about a week of the 1935 tour starting, a display was given at a location east of Birmingham, which may have been Coleshill. At the conclusion of the day the Clive, like all the other aircraft, was refuelled by the National Benzol truck so it could fill its tank at a depot and appear in time wherever the next display was scheduled on the itinerary.

Topping up with oil was left as a staff warm-up exercise for the next morning. The Bristol Jupiters being oil-cooled in addition to any air which might waft across their cylinders, meant carrying 4 gallon drums of Castrol, as advertised, two at a time by the wire handles on top of the drums. The Bristol rep., Reggie Knapp, with an eye conditioned by experience in South America, Africa, Japan and elsewhere, ensured that what had to be done was indeed done. Capt. H C Johnston who, given an aeroplane small enough could have flown through a fishing net, surveyed his modest load with an experienced eye. Reggie suffered from claustrophobia, so always flew in the open cockpit with the Captain. The toolboxes, passenger boarding steps, cleaner's ladder, the loader, Ted Watling, myself, and a large ex-London Constable who had joined as a display policeman only the previous day and had never flown in an aeroplane before, occupied the passenger cabin.

The field was rectangular and had lent itself to the long dimension on the previous day. But not this particular morning. A very brisk westerly was blowing. With his long experience on Handley Pages of various types, the Captain knew that resistance to cross-wind component was not the outstanding feature of the Handley Page drawing office. He therefore opted for a diagonal compromise in take-off direction.

As usual, the Clive got airborne in a very short distance but, with a massive thud and yaw, uprooted a smallish tree with the outer starboard lower mainplane. The Clive continued with a slight climb and a series of mild yaws. Reggie overcame his claustrophobia long enough to come aft and advise that the aileron controls were jammed. This didn't mean anything to the policeman, but his gazing out of the window at a tree festooned around an outboard interplane strut, and the shedding of leaves in the breeze, had obviously conveyed to him that all was not well.

Fortunately, just a few miles ahead, and dead on track, lay Castle Bromwich airfield which at that time was also an RAF station. With as expert a piece of flying as one is likely to see, and in gusty conditions, Hugh Johnson maintained lateral control by judicious applications of rudder, and landed at Castle Bromwich dead in line. No runways in those days. Possibly the RAF, seeing so much flying vegetation, thumbed through their copies of 'Macbeth' to refresh their minds about the portent inherent in the Forest of Dunsinane.

When, with feet on comforting ground, we stood and surveyed this botanical air-brake, Captain Johnson, a man of few words, said "Jesus of Nazareth" and strode off with signs of displeasure. Shortly afterwards the policeman also departed the scene.

The tree trunk was about five inches in diameter where it had broken off. It had bruised the front spar. A lower bough had bent the push-rod operated aileron horn 90 degrees outboard, effectively locking the aileron control, and the rear spar was damaged beyond repair.

Thanks to Captain Johnson's old boy network we got excellent assistance from the RAF. Back at Ford Airfield there were enough surplus Hinaldi wings to cover a football pitch. One was rapidly sprayed silver over its Mesopotamia drab and, with other spares and stores, despached on a semi-trailer with escort because of its size. We were flying again three days later. The biggest job was painting the missing registration under the replacement wing.

Part 5 - The Wingless Wonder

The above wording was the official air display name for the C30 Autogiro, spelt with an 'i' by the company that developed them. Autogyro, with a 'y', appears to be the generic name for that type of aircraft. Among the predominantly male display staff it was frequently referred to as the 'whirling spray'.

Previous displays had operated the earlier C-19 model with a four-bladed rotor, twin fins and a low wing with upturned tips. The C-19 has a susceptibility to ground resonance, the so-called 'Dance of Death', causing a number of incidents resulting in major damage, but otherwise harmless to occupants.

The C-30 was different. It had a three-bladed rotor, no wing, a more powerful 140hp engine with a rotor run-up clutch, a robust undercarriage and an entirely different control system.

At Phoenix Park in Dublin the autogiro made more than 100 joy rides on the same day (at a premium ticket price too), the Display Manager going not so quietly mad every time that the aircraft stopped for a blade drag check.

On one ocasion at, I think, Cannock Chase in Staffordshire, Captain Ashley was giving his usual solo demonstration of the wingless wonder. Tailwheel on the ground, wheels nearly two feet off the ground, the aircraft rolled along the flight line looking like a parying mantis with its antennae in a spin. The area was prone to mining subsidence. At the end of the line the right wheel struck a vertical wall of local landscape, concealed by long grass. The gear was broken off and the autogiro fell on its right side as it came to a sudden stop. As the still spinning rotor went round, the landscape repetitively sheared off the blades - about a yard at a time, the bits flying in all directions.

The Show went on. We had a replacement autogiro the next day, on hire while YH departed for major remedial surgery. Which didn't take long either, Display Management being somewhat sensitive to any sort of cost. Particularly hire costs.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)